Ecological Arbitration and the Universal Mind

Preface

This essay began as a follow-up to my previous piece — The Enshittification of Nature and the Limits of State Intervention — on the limits of existing nature finance paradigms. It turned into a dissertation-length set of musings that discuss the rights of nature movement, the supposed need for ecological democracy, and the issues economic approaches exhibit when attempting to arrest present climatic-ecological crises. It is filled with footnoted qualifications and mitigations — partly representative of my inner dialogue — and manages to link Trotskyite and Hayekian thought with humanity’s management of ecological systems.

The essay is split into four chapters, each of which can be read individually and one at a time (although I would encourage reading them in sequence). They are as follows:

1. The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis

2. Legal (and Democratic) Arbitration

3. Economic Arbitration and the Universal Mind

4. An Ecological Subsidiarity?

Do enjoy, and let me know your thoughts in the comments below or by popping me an email.

The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis1

The history of humanity is a history of ecological domination: the domination of non-humanity, of non-humans. The ecosystems we have inhabited and continue to inhabit have been morphed — manipulated — beyond recognition, shaped to cater to human needs and desires. We have razed forests, ploughed grasslands, emptied and acidified oceans; we have eutrophied water bodies, polluted the air, and forcibly displaced — if not exterminated — countless species through direct exploitation and habitat destruction. This history is universal, differing only in extents. Palaeolithic communities exterminated megafauna through concerted hunting campaigns; Han dynasty China deforested upland forests to such a degree that subsequent eroded silt flows formed the land Shanghai sits on today; and early modern indigenous communities in northeastern North America — and, in fact, across the continent — participated in a fur and hide trade that decimated fur- and hide-bearing non-human species.2 This pattern is visible no matter what human community is examined in whatever period of time it may be examined in — expressing a spatiotemporal dominance that has allowed, and continues to allow, humanity to alter its environs at will.

The source of this dominance fills volumes. Scholars have attempted to locate ecological relations that expressed otherwise — departed from for whatever reasons the subjects of that study may have had. These attempts embody a (fruitless) Edenic approach, searching for a supposed baseline human-non-human harmony: when and where was that apple picked from its tree, and who or what was the snake that convinced Adam and Eve’s derivations to do so? The snake, here, embodies epistemological, organisational, and technological changes.

Epistemological reasonings for spatiotemporal dominance focus on shifts in how human communities thought about their relationship(s) with non-human beings and the natural world.3 These reasonings typically argue that a shift in relational thinking — one wherein human communities see themselves as a part of a greater, fragile, whole that needs to be, at least to a certain extent, both selfishly and selflessly preserved — to mechanistic and dualistic thinking — wherein ecosystems and their constituent non-human beings are seen as entirely separate and purely as ends to human needs, and nothing more — brought us to where we are today.4 Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is often cited as a set of epistemologies we departed from; Cartesian dualism and Judaeo-Christian monotheism as epistemologies we transitioned to, amongst others.

Organisational reasonings supplement these, supposing that the ways human communities organised themselves, the ways in which they allocated resources, and the ways in which they made decisions resulted in their historic domination of the non-human world. Organisational reasonings narrow epistemological equivalents — placing emphasis on their practical implementation.5 A mechanistic way of thought that reduces the natural world into atomistic parts that serve discrete purposes for human communities, for example, could be and in fact was translated into economic models that took that thinking as their basis. Systems that focussed on the accumulation of capital, and the maximally — numerically — efficient distribution of resources, were informed thereby; non-human actors viewed as own-able entities to be endlessly exploited, their agency stripped in entirety. Equally, legal systems, taken as reflections of our social norms and cultural values, emerged and morphed, placing pre-eminence on the needs and desires of the singular human over the ecological whole. And political systems, particularly representative political systems, led to the prioritisation of their human constituents’ interests — the historical exclusion of specific human interests being anthropocentrically demonstrative of this fact.

Technological reasonings fit into both epistemological and organisational frameworks, usually succeeding the former and preceding the latter.6 The discovery, creation, adoption, and use of technologies, so the logic goes, was informed by epistemological shifts (or often mere historical accidents) that subsequently reshaped human communities’ relationships with space and time. Technologies are ultimately spatiotemporal compressors, allowing human communities to impose their wills over greater swathes of space in less time than they were previously able to — particularly relative to their non-human counterparts. The technologies in question varied: compressors can be as simple and primitive as spears or bows and arrows, which increased hunting efficacy. They can also be as complex as the carriers of people and information today, encompassing physical and digital infrastructure. They can, too, seem inherent: the use of language, particularly in written form, bridges time and therethrough allows for accumulated learning. Whatever the technologies in question might be, human communities’ abilities to impose themselves grew; the ways they organised themselves, then, adapted accordingly — expressive of the need to manage their expanded reach.7

Whether the creation and adoption of technologies that alter our relationship with the natural world is inevitable — this being itself much-debated, with some arguing that their development and use are phenotypical expressions — the fact of the matter is that this very relationship has been deeply altered, irrevocably.8 Obsessing over precise points of departure — and calling for the reversion thereto — is not necessarily constructive. Instead, we should obsess over the (continuous) symptoms of departure. We should obsess over the ways human spatiotemporal dominance is managed; how our expanded ability to choose or not choose to make particular decisions that impact fellow beings is arbitrated. Without invoking the clichéd metaphor — because it would be undue to refer to humanity’s spatiotemporal penchant as a disease — it is easier to treat and target symptoms when their cause is unresolved.

Ecological systems arbitrate decision-making and resource allocation simply. They play discrete actors against one another; competing, cooperating, often melding into one or two (or more); selfishly interrelating for their own benefit, to perpetuate — knowingly or unknowingly — their genetic substance. Each actor is, relatively speaking, bounded — their spatiotemporal influence correlated, in the short-term, with the bounds of their body. To be clear, these bounds are hardly absolute. Think of beavers and their dams, termites and their mounds, or dolphins and their use of tools. I am not attempting to promote a unitary view of biology, yet actors’ interconnection and interdependency should not be mistaken for a complete lack of discreteness.9

Ecological and planetary history is dictated by this sometimes orderly, sometimes chaotic, never-quite-predictable system of arbitration. Simple phenomena like carrying capacity are classic examples, with actors competing for resources across space over time. If one is able to impose themselves over greater space in lesser time, they may access more resources — to their and their progeny’s benefit. That is not to say that these systems operate in equilibrium — far from it. But the rules those disequilibria abide by are ecologically fixed; the equilibrium in question is dynamic.

This is a flexible model. It is not hard and fast; nor is it drawn from any specific theory of ecology. It is instead a description (or definition) of ecology itself, of how ecological actors interact and interrelate. Exceptions are most obviously temporal: species’ bounds change as they evolve, and as they recursively niche-construct the environments they inhabit. Species’ influence, too, is not necessarily correlated with their individual reach — one only has to refer to perhaps the most positively consequential event for aerobic life in this planet’s history: cyanobacteria’s collective oxygenation of the Earth’s atmosphere.

This model illustrates humanity’s superseding of ecological systems with its own; the replacement of ecological communicational systems — wherein actors’ wants and needs are allocated according to the uninterested hand of evolution and species’ preferences are expressed purely by their ability to impose them — with human communicational systems; wherein each element, each actor, is willessly assigned representational values according to human wants and needs.10 And those representational values, mirroring the human organisational systems they derive from, are legal, political, and economic.11

Those values, here, equate to the weight actors are assigned.12 These weights are influenced by all sorts: the utility, whether practical or aesthetic, that actors serve; actors’ abilities to communicate (in the literal sense) their preferences, or have their preferences be interpretable in the first instance; and the power actors embody — their direct influence over human affairs.13 The corresponding value actors are assigned in organisational systems can include particular statutory or fundamental legal rights, say, or a literal dollar value when economically allocative decisions are made.

By emphasising communication between actors, and how actors’ differing preferences are arbitrated, we can begin re-altering — or rather de-altering — our relationship with the natural world. We should focus on how we communicate rather than what we communicate; not on the content of that which we shout at non-human beings, but on the fact that we shout at them in the first place (and what enables us to do so). By doing this, we can realise that our shouting is both unproductive — harming our relationship with the natural world, and thereby ourselves — and far from inevitable. Our vocal range is not permanently set to its present maximum volume; it just so happens to have found itself where it is today through the contingent discovery, creation, adoption, and use of particular technologies. Just as we have raised our volume, we can lower it.

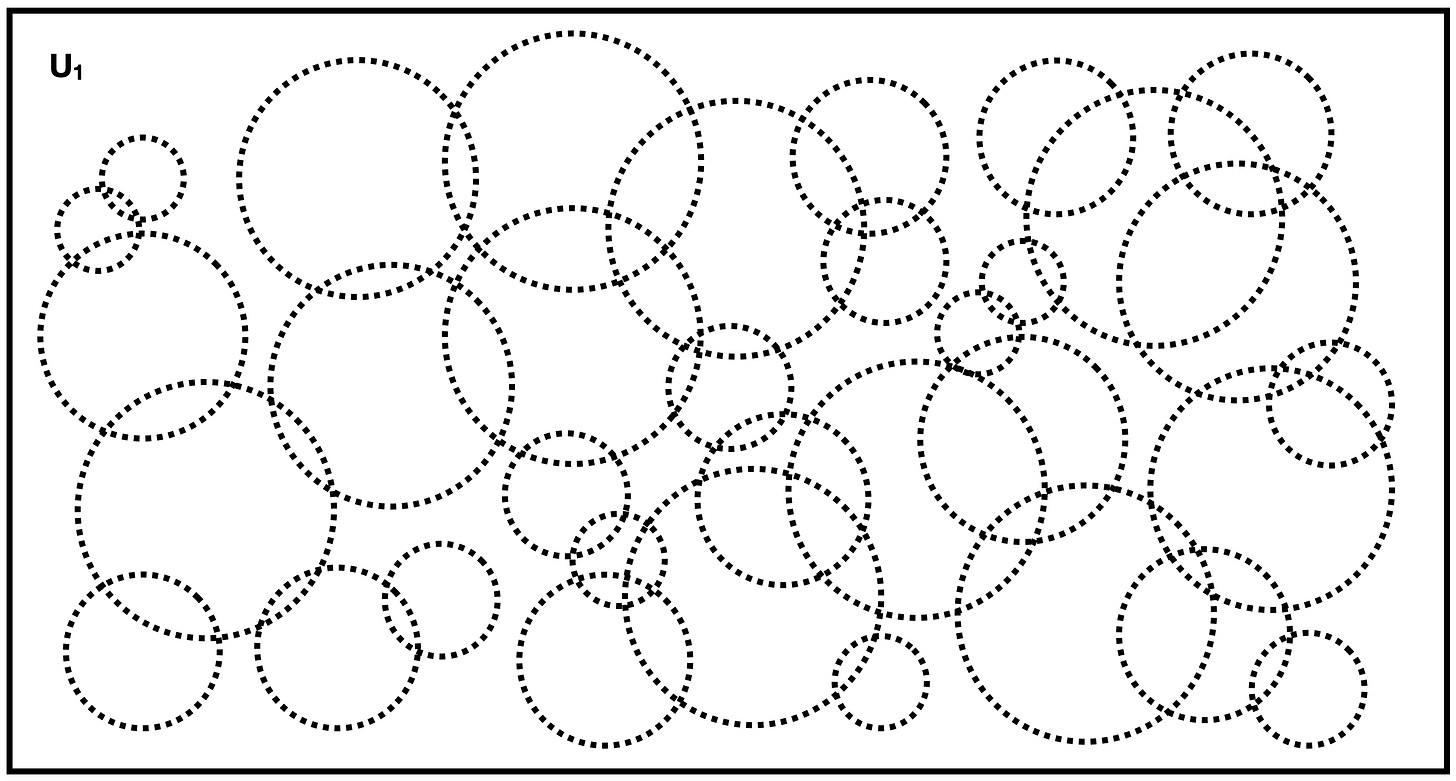

Before going on, I thought it would be useful to visualise the communicational breakdown I have outlined above. In the below diagram, each permeable circle is representative of an ecosystem actor. Circles interrelate and overlap, being simultaneously dependent on and independent of one another. No permanent order exists — imagine each circle vibrating continuously, bouncing off the walls of the universal set much like we bounce off the walls of the planet we inhabit. Despite this, each actor, each circle, is identifiable in a particular instance; they and their bounds are relatively discrete — aligning with their ability to impose.

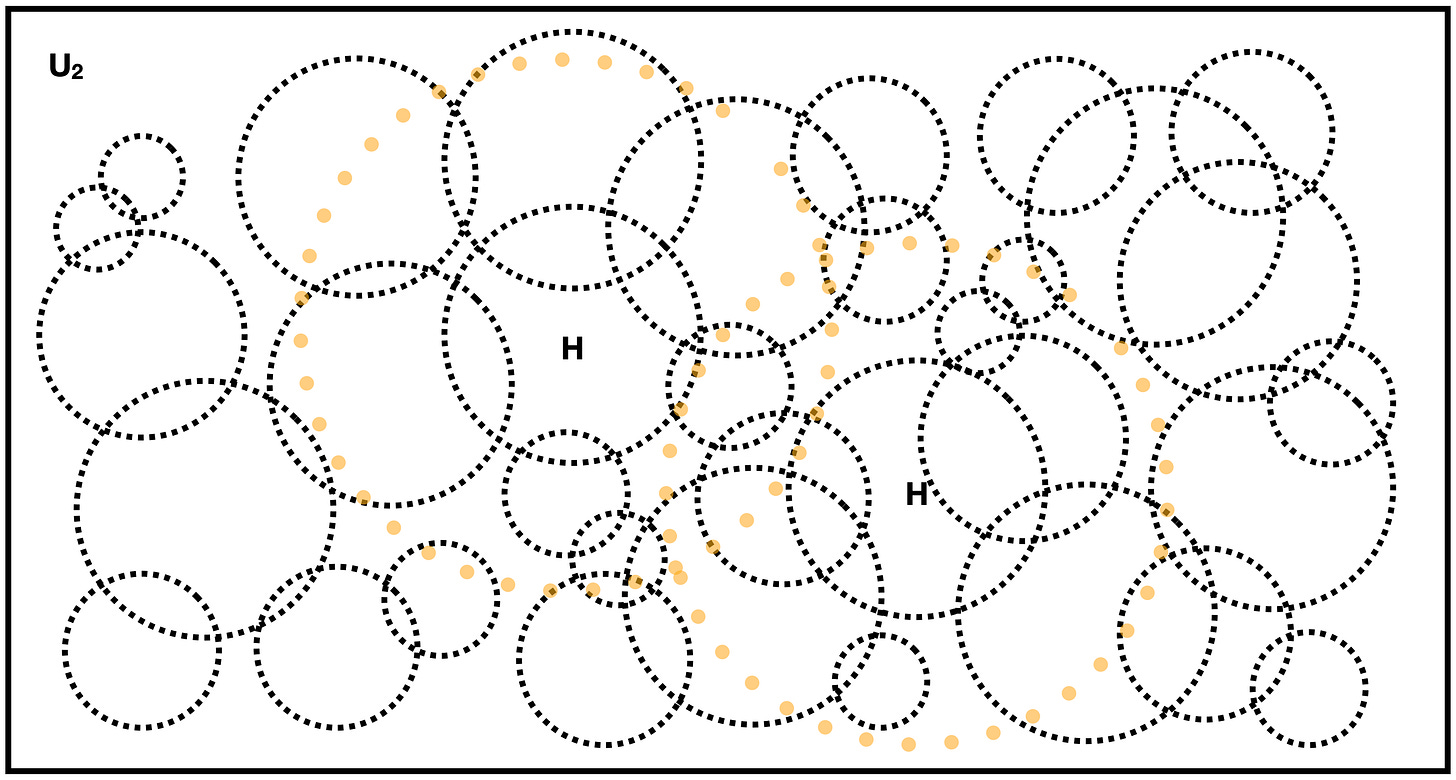

In this second diagram, the bounds of two human communities have been identified. Secondary circles around these communities have been added to illustrate their expanded ability to impose themselves on fellow non-human beings, following the adoption of particular technologies over any one period of time. These secondary circles or additional bounds are not hard, much like the bounds that they supersede. They are permeable and in flux. They overlap the literal and figurative ecological space taken up by other ecosystem actors — and it is this space that humanity’s organisational-communicational systems attempt to manage, having supplanted their ecological predecessor. And it is this management that presupposes poor ecological outcomes.14

Countless critiques have framed our present position in this way. The form and function of extractive, capitalist, statist, or planned economic systems have been assigned blame for the climatic and ecological crises we are experiencing today; as have the form and function of present legal systems, or those of representative or totalitarian political systems. Alternative organisational arrangements to these have been floated. In my previous essay on these matters I looked at two such economic — natural capital-geared statist and private actor-driven — alternatives. I will now look at alternative legal and democratic arrangements, as well as economic arrangements in a broader sense. I focus on rights of nature approaches, ecorepresentationalism, and a variety of economic frameworks, with the aim less to critique these approaches in isolation — although I definitely engage therein — and more to use these critiques to make a larger argument about the ways human organisational frameworks are imposed on the ecologies we inhabit and live alongside. I will set out why proposed reforms to existing human organisational-communicational systems are intrinsically unable to arrest the continued degradation of Earth’s biosphere. My intention is to focus on the mechanics of human organisational-communicational systems, and how these mechanics’ incongruity with their ecological counterparts makes them an ill-suited set of solutions. My interventions serve as a springboard to marry the thinking of the seemingly incongruous Leon Trotsky, Friedrich Hayek, and James Scott — applying the idea of the universal mind in an ecological context.15

Legal (and Democratic) Arbitration

Legal systems exist to moderate — arbitrate — relationships; they exist to lay down a set of ground rules that actors the systems encompass must abide by; and lay down a subsequent set of ground rules that allow for conflict resolution should those rules be ignored.16 They, then, essentially act as a communicative system between human individuals and organisations. For non-human actors, they assign representational value in two ways: by granting specific legal protections that must be considered when public and private decisions on resource use and allocation are made; and by giving actors legal standing in themselves, however conceived. The former statutory route — think of the Endangered Species Act in the United States or the Habitats Directive in the EU — has had mixed success (look at the state of the natural world today).17 The latter route has subsequently received more attention in recent years, with some proponents arguing that environmental wrongs are attributable to the wronged’s lack of legal standing.18 Viewed this way, climatic and ecological collapse is partly a legislative failure — the refusal to integrate and thereby listen to non-human needs in our decision-making structures. Decisions to, say, hunt blue whales, were and are the result of their not having particular legal rights — a direct result of their not having democratic rights to ensure these. Equally, decisions to dam river deltas or raze forests to the ground were and are the result of these ecosystems not having legal standing of any kind, nor a chance to make the case for this. Our backdrop is thereby one of ecological tyranny.

The logic, then, follows that if non-human constituents of the planet we inhabit would gain representation, and would by extension gain rights to life and non-harassment, the polycrisis we face would disappear — or at the very least peter out. Such is the thinking of the rights of nature movement, a subset of earth jurisprudence, framing the issue as one of both a basic moral cause and as a recognition of other species’ ecosystemic utility. This is typically expressed by the idea of legal personhood — considering the natural world’s actors as legal persons with the same rights as other juridical persons.19

Proponents point to a number of successful examples, the most famous among these being the TEK-informed Ecuadorian Constitution. Its articles, 71 to 74 in particular, clearly outline not just the rights of ecosystems and their constituent species to protection against harm, but the rights these ecosystems and their constituent species have to restoration following historical harm. Human communities, too, are granted a clear right to a healthy and healthful environment. These provisions have repeatedly shown teeth. The most recent example of this was a case concerning the country’s national mining company, Enami EP. Prospective copper and gold mines in Los Cedros — a protected cloud forest in the north-west of the country — were ruled to be violating the constitutional rights of the forest and its inhabitants. The mines’ permits were withdrawn after local communities took the case to the Supreme Court.

Other examples that rest on indigenous relational understandings of the natural world exist too. The Māori and the Kiwi government granted the Whanganui River personhood in 2017, with the Māori having regarded them as a common ancestor to be protected. The Yurok of present-day California replicated this in 2019, granting the Klamath River — recently undammed and now free-flowing — legal personhood in their tribal courts. The Ojibwe White Earth Nation of present-day Minnesota echoed another aspect that same year: the rights of human beings to a healthful environment. Wild rice, or manoomin, deserved legal protection to ensure the continued wellbeing of the Nation’s descendants.

Legal systems are inseparable from their political antecedents. They draw their legitimacy therefrom, relying on attestations of sovereignty to ground-truth their judgements. The exclusion of all but one of the biosphere’s constituents undermines that ground-truthing from the outset. The need for an ecorepresentational law, as described by Jonathon Keats at the Earth Law Centre, is thereby . Non-human actors necessitate standing in the political structures that influence the legislative outcomes which affect them.20

Whether democratic or otherwise, non-human worlds are as political as ours. Female African buffalo, for example, have been recorded standing and staring in particular directions and sitting back down for (seemingly) no apparent reason. This is in fact an expression of a voting mechanism that dictates herd movements — once a majority of buffalo stand up and gaze in the same direction, it becomes their direction of travel. Similar behaviour is exhibited by herds of red deer — they typically only move after Rule XXII of the US Senate is met: more than 60% of adults must stand up in agreement.21 Flora and fungi also exhibit democratic tendencies, famously collaborating and distributing resources via mycorrhizal networks that equitably redistribute resources according to need — a kind of congress of trees. Autocratic expressions in the non-human world exist too. Chimpanzees’ sometime-reliance on brute force bypasses the coalition-building ballot box, while spotted hyenas’ elevation to rule is determined by lineage — a quasi-monarchy of sorts. Examples of integration between human and non-human political worlds, though, are limited, precisely because it is difficult for non-human actors to communicate their preferences in the human-expected form, and because their integration would be presupposed by a willing direct loss of control by humans themselves (more on this later).

Partly because of this, it is illusory to think that rights of nature as a model can address the sheer ecological poverty of the present day — remedying it and bringing us into some utopian nirvana of coexistence and harmony. Seen this way, the approach has some fatal flaws; flaws that are particularly fatal if the desired end goal of the approach’s implementation(s) is that of restoring not just ecological intactness, but function and dynamism too. These fall into two categories: fundamental concerns relating to its logic; and more practical concerns relating to its application. Let’s address the approach’s practical concerns first.22

Presently, different human actors with differing resources bend the law to their will, able to afford better representation and take proactive legal action in their favour. There is inbuilt inequality, although this can at times be partly mitigated when legal aid schemes are well-resourced. The lack of representation non-human actors would and do receive in legal systems imbued with rights of nature would mirror that seen in purely human legal systems. Whether it be in civil or criminal cases, those with more cash afford themselves greater privilege. It is hard to imagine a system wherein resources would be actively and at scale reallocated to those — non-humans — with a greater need that we can hardly relate to in the first instance.23

Litigative knowledge gaps are a major difficulty too. These are twofold: the first is the lack of evidence to pursue civil or criminal cases; the second, relatedly, is the lack of knowledge that cases can be pursued in the first place: whether actors who are the victims of uncivil or criminal behaviour know, and can communicate, that what has been done to them can be remedied in court — or whether someone (a human) can know of those happenings and pursue remedies on their behalf. Our understanding of relational ecology, wherein we fully comprehend and can model the interactions between varied ecosystem actors, is limited. Given legal systems are essentially formal processes that arbitrate between human actors (relying on the knowledge of how those human actors make and weigh decisions) translating the limited understanding we have of non-human actors into these systems is unwise.24

The integration of non-human interests into human legal systems is, too, entirely dependent on our willingness to surrender control — to gift, to grant, rights to those who cannot otherwise fight for them. This is given the fact that legal systems are derived from their political equivalents — the assignation of rights is dependent on those being assigned rights’ ability to participate politically. A reformed legal system that would, then, give non-human beings rights without their ability to substantively comment thereon is inherently flawed — we would be assigning rights to the mute. And a reformed legal and political system that would grant non-human beings respective rights and representation would involve a ceding of sovereignty and control that is hard to envision. Sovereignty (typically) arises from a monopoly on violence — which, in this case, humanity would maintain through its spatiotemporal dominance. That ceding, then, would have to be the result of a benevolence that is continuously and vociferously maintained.25

Even considering a surrender of sovereignty, the necessary direct communication of non-human constituents’ interests is essentially impossible. Our knowledge of ecosystems and the actors they consist of is deeply limited — we’ve hardly catalogued all species on earth, hardly understood all their functions, and are hardly able to calculate their respective needs and desires. Advancements in technology that would allow us to listen to non-human counterparts — like current artificial intelligence-fuelled projects that look to decode sperm whales’ language — may well part-solve this.26 But they ignore the fact that even those we can and do communicate with face systematic discrimination and destruction: look to any human-on-human genocide in history for evidence thereof, including those taking place in the hyper-communicative world we live in today. They also ignore the fact that human-non-human communication may take place in bad faith — what is to stop justifiable vengeance for past wrongs being taken by non-humans through deceptive means?

Another practical weakness that alludes to the fundamental challenges integrating the natural world into our legal systems pose is the weighing of ecosystem actors’ interests against each other — not just the weighing of their interests against ours. Weighing human against non-human demands is relatively simple: don’t raze the forest to the ground, or don’t blast that bit of seabed.27 Doing so would be a clear violation of non-human interests — essentially an act of ecological genocide; ecocide. But what about the interests of an orca pod, or an individual orca, against a seal’s? How would a legal system decide whether hunting is justified?28 Enforcement is another question, but the integration of what are essentially value judgements — moral frameworks — complicates matters greatly. Zooming in on these kinds of micro-incidences is useful. Take dredging, for example, an act that is clearly egregious. How does this compare with the hand-diving for scallops? What about mass mechanised deforestation relative to the cutting down of a single tree by an individual wishing to extend their existing home, or redesign their garden? Ecocentric thinking is inherently fluid and context-dependent, but integrating it concretely into the law means that this fluidity has to disappear: statute books tend not to be vague.

And whether reliant on statute books or on the setting of context-dependent principle-derived precedent by individual or panels of judges, the same problems remain. However vaguely defined — this could take the form of a right to life without undue harassment; or a right to existence in the first instance — judges would have to weigh those rights against others’. The human right to shelter, say, might conflict with an oak’s right to existence; or the human right to adequate food could conflict with an ecosystem’s right to exist on soon-to-be converted arable land. It takes time and deep knowledge to weigh these rights against one other — knowledge that judges and even trained ecologists do not have (given the value judgement involved) and time that the biosphere does not hold (given the acute crises it is in). Precedents take decades and centuries to settle; not months or years. The lack of specificity proffered by the use of fundamental rights is thereby a major barrier to their successful implementation.

Judgements that would arbitrate actors’ competing interests thereby have to consider and somehow measure, at all times, the public — or rather the planetary — interest. A greater interest of any kind always contravenes on lesser interests of other kinds; the interests of a landowner to garden peacefully may be challenged by the interests of the public to build a train line through that very garden; the interests of a river or a forest to exist unobtruded may be challenged by the interests of a parallel river or forest to expand, or the interests of a nearby human community to build a school in their vicinity.

This leads us to another key weakness. Legal systems are static, and enforce staticity.29 Their function is to maintain a particular state and a particular set of rules — they hardly allow for or enable the dynamism present in natural systems. Giving a river rights, for example, is hard to square with the needs of that river to move in future: if its wiggling and turning results in the contravention of other actors’ interests, how would a legal system deal with those? A tree, say, that would have its root system drowned by that river’s movement would rather not have it move.30 This gets to the core mismatch between legality and ecology — ecological systems presume no total oversight, nor the possibility of total knowledge: they rely on different actors having different interests and squaring those interests off against each other in bounded space and time — the sum of those interactions resulting in ecosystems’ ebbs, flows, and shifts.31 Legal systems’ staticity becomes particularly acute when large exogenous shocks, be they climatic or cosmic, come along. Their disruption leads to the total rearranging of constituent actors’ makeup, but legal systems’ predisposition to preserve the status quo — in that they exist to preserve participant actors’ interests — means that the reconstruction of ecosystems and habitats would not follow existing contexts — the now non-existent, previous, context would be forced. Given legal systems’ dynamism is partly fed by political — and in this case democratic — sources, it is difficult to imagine one where constituents that make up those sources would willingly permit a change in circumstances that would detrimentally impact them; unless violently overthrown by new or newly-empowered constituents.32

Economic Arbitration and the Universal Mind

Much like legal systems, economic systems seek to manage the spatiotemporal dominance that humanity exhibits. Much like legal systems, economic systems seek to regulate interactions between different actors through a set of predefined rules, or assumptions. And much like legal systems, economic systems superimpose preferential human-human communication on the non-human world.

These comparisons stand no matter what economic school informs its namesake system. The dichotomous approach taken in my previous essay on enshittification and state intervention is an example thereof. State-centric organisation relies upon centralised knowledge to function; the ability to estimate, if maximal efficiency is the goal, the value judgement-free wants and needs of the system’s constituents — whether companies, public bodies, or individuals. Distributed private actor-centric organisation that places a greater emphasis on decentralised knowledge doesn’t necessarily augur better outcomes — decentralised knowledge faces the bottleneck of being less able to adequately calculate the externalities that transactions, or communications, between individual actors involve, and the system as a whole is unable to incorporate the individual knowledges held by non-human participants (or rather subjects).

Even alternative systems of economic governance — whether ecological or otherwise — fall victim to the same problem. No system can, and this applies to legal equivalents too, track, calculate, and equitably cater to the wants and needs of the disparate actors it encompasses. (Human) systems, by default, rely on their being a superimposition — prioritising the needs of some over the needs of others.

Economic systems, at their core, seek to universally manage their constituents. They seek to manage the resources that form their basic factors of production, land and capital in particular. They seek to assign ecologically arbitrary values on those factors that enable their efficacious use. Whether those values are assigned by a central economic actor or by the playing off of diffuse (differently placed) actors, an overriding organisational imperative applies — and an overriding exclusion of non-human actors, considered either as animately or inanimately valued material, exists.

It is this exclusion which tends to be the focus of natural capital boosters and grandees alike. It is too often forgotten that assigning a value — one assigned either by the state through regulatory reform, or willingly-so by private actors to, say, bolster the integrity of their supply chains — fundamentally dehumanises, or rather essentialises, living, biotic, beings. Their value, beyond being representative of an imposed construct — and we as humanity have a poor history of imposing human financial-value constructs (refer to our long history of slavery here) — will be optimised, relentlessly.33 I have already discussed this at length elsewhere, so I won’t needlessly repeat myself. It should regardless be noted, though, that we have an inherent inclination to exploit rather than respect a value. Once numericised, actors are taken advantage of (for better or for worse), the actual or potential non-numerical value they once held purged.34 Actors, in this sense, are not actants; they are nominal instrumentalised actors, directed around the stage rather than being granted the agency to do so of their own accord.

If one envisions an overlapping of systems, much like we have in the human domain today, of legal, political, and economic structures, the necessary dynamics that would underpin these alternative forms of organisational communication are clear. If actors held only legal and no political and economic representational value, they would quickly lose it. To guarantee legal representational value, one must hold political representational value; and to guarantee political representational value, one must hold the economic representational value — the power — to ensure and maintain it. But to ensure one is granted economic representational value — given this granting is at the discretion of the spatiotemporally-dominant actor — one must hold political representational value; and to hold political representational value, one must first hold legal representational value. These chains of reasoning are not ironclad, but the point I am trying to get across is simple and worth repeating: for non-human integration into human organisational-communicational systems to be viable, human sovereignty must be willingly and continuously ceded. Human spatiotemporal dominance requires utilising that dominance charitably.

I have argued previously that this charitability is hard to envision on the scale necessary to arrest ecological decline. But if it was a possibility, charitability would be needed on all three fronts. It is not sufficient to grant only economic representational value, or only legal or political representational value. It is an all or nothing.35 Economic value alone presupposes abuse — one only has to imagine the horrors of a world where actors (and human individuals) are represented thereby.36 Legal or political value alone presupposes a snubbing — a disregard reflective of their lack of unwritten power.

Whatever the combination of superimpositions may be, all align with the concept of the universal mind; the idea of the total management of the earth’s biosphere through complete and constant knowledge of its constituent parts and mechanics.37 This alignment is a physical fact — humanity’s spatiotemporal dominance presupposes the development of organisational frameworks that imperfectly attempt to manage that dominated time and space, and the actors that interact therein. Whether or not those organisational frameworks intend to manage time and space to the extent they do, or whether they intend to embody universal minds, our spatiotemporal dominance presupposes their defaulting thereto.

Total management is an impossibility. Leon Trotsky realised as much in 1932, writing after his banishment from the Soviet Union and the Communist Party. Describing the universal economic mind in the context of a planned economy and the dynamics of a free market, he wrote:

‘If a universal mind existed … that could register simultaneously all the processes of nature and society, that could measure the dynamics of their motion, that could forecast the results of their inter-reactions — such a mind, of course, could a priori draw up a faultless and exhaustive economic plan, beginning with the number of acres of wheat down to the last button for a vest. The bureaucracy often imagines that just such a mind is at its disposal; that is why it so easily frees itself from the control of the market and of Soviet democracy. But, in reality, the bureaucracy errs frightfully in its estimate of its spiritual resources. … even the most correct combination of all these elements will allow only a most imperfect framework of a plan, not more.

The innumerable living participants in the economy, state and private, collective and individual, must serve notice of their needs and of their relative strength not only through the statistical determinations of plan commissions but by the direct pressure of supply and demand. The plan is checked and, to a considerable degree, realised through the market. The regulation of the market itself must depend upon the tendencies that are brought out through its mechanism. The blueprints produced by the departments must demonstrate their economic efficacy through commercial calculation.’38

Trotsky was writing a critique of excessively-centrally-planned economies, but transposed onto the historical context of human-non-human relations and the imposition of any economic system and the imposition of legal and political systems on our biosphere as a whole, this critique still stands — and is in fact strengthened. The legal, political, and economic communications of ‘living participants’ cannot, as I have discussed, be represented — nor can those communications be assumed by central bodies. Any attempt to do the latter results in an ‘imperfect framework’; an uncertain framework the uncertainty of which multiplies, and thereby worsens, through its continuous application. Any attempt to do the former — and this is where I disagree with Trotsky’s seeming acceptance (at that time) of lesser-planned economies when transplanted into an ecological context — results in individual misrepresentations that similarly multiply and come crashing down.

Trotsky’s description ironically aligns with Friedrich Hayek’s diagnosis of the same problem; that of inter-actor communication — or what he called the local knowledge problem:

‘Today it is almost heresy to suggest that scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge. But a little reflection will show that there is beyond question a body of very important but unorganised knowledge which cannot possibly be called scientific in the sense of knowledge of general rules: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. It is with respect to this that practically every individual has some advantage over all others because he possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made, but of which use can be made only if the decisions depending on it are left to him or are made with his active cooperation. We need to remember only how much we have to learn in any occupation after we have completed our theoretical training, how big a part of our working life we spend learning particular jobs, and how valuable an asset in all walks of life is knowledge of people, of local conditions, and of special circumstances. To know of and put to use a machine not fully employed, or somebody’s skill which could be better utilised, or to be aware of a surplus stock which can be drawn upon during an interruption of supplies, is socially quite as useful as the knowledge of better alternative techniques. And the shipper who earns his living from using otherwise empty or half-filled journeys of tramp-steamers, or the estate agent whose whole knowledge is almost exclusively one of temporary opportunities, or the arbitrageur who gains from local differences of commodity prices, are all performing eminently useful functions based on special knowledge of circumstances of the fleeting moment not known to others.’39

I encourage you to re-read that passage with an ecological eye. The specific knowledge any particular economic actor might hold in any one instance, or in any one ‘fleeting moment’, is much the same as that which any ecosystem actor may hold at any one time — and be capable of imposing. And the knowledge economic actors each build up over time — whether through ‘theoretical training’ or in their ‘occupation’ — is much the same as that which ecosystem actors are bestowed by virtue of their genetic code and through their lived experience. Hayek, specifically, was arguing against the idea of a Central Pricing Board, a theoretical economic arbitrator that partly sets goods’ prices and allocates investment and capital. The Board, here, is whatever human organisational framework is imposed upon non-humanity. Hayek goes on:

‘One reason why economists are increasingly apt to forget about the constant small changes which make up the whole economic picture is probably their growing preoccupation with statistical aggregates, which show a very much greater stability than the movements of the detail. The comparative stability of the aggregates cannot, however, be accounted for — as the statisticians occasionally seem to be inclined to do — by the “law of large numbers” or the mutual compensation of random changes. The number of elements with which we have to deal is not large enough for such accidental forces to produce stability.’40

Were Hayek ecologically-inclined, he would here be critiquing economic communicational systems specifically; targeting both totalising statist approaches that seek to integrate and act upon all knowledge simultaneously — or unintentionally effect as much — and distributed approaches that impose a central operating system; a set of artificially programmed rules for actors to abide by. Universal mind-ism — the converse of the local knowledge problem — pervades the way humanity manages, relates to, and seeks to re-relate to the natural world. To lean into James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis’s Gaia, it is as if the planetary body, made up of disparate limbs, organs, and microbiota, was run by a single synapse (framing humanity’s interpretive capacity as even lobe-worthy would be a stretch). Replacing that synapse with another, or even adding a few more to it, cannot and will not restore full bodily function.

This is a somewhat imperfect metaphor, given that I have essentially been arguing that each disparate body part acts and should be able to act according to their own mind. Regardless, as soon as those individual minds become subsumed by a greater mind, by the universal mind, the system breaks down. James Scott describes this problem in a human-epistemological sense in his Seeing Like a State. His equivalent of Hayek’s local knowledge is metis — the product of the ‘fleeting moments’ and years of ‘theoretical training’ that make up the practical knowledge embodied by individual actors and communities. Shaped by its respective contexts, it stands in contrast to what Scott called ‘epistemic’ knowledge — a set of formalised and less-flexible knowledge typically derived from and associated with the scientific method, alongside formal educational instruction. This ‘epistemic’ knowledge is centralised and standardised, an ocean away from the individualised, respondent, context dependency of metis.

This process of centralisation, standardisation, and the correspondent totalitarian impulses that accompany a claim (or series of claims) to truth can be neatly mapped onto ecology; onto the millennia-long ongoing process of human-induced ecological subsumption. Our imposition of rigid organisational frameworks — whatever epistemic bases they may have — by design disregards and marginalises individual ecosystem actors’ basic ecological operation, and their own individual claims to truth; their own metises. The agential breakdown Scott outlined — whether in Germanic silviculture, the simplifying urbanity of cities like Brasília, or the collectivisation of Soviet agriculture — intimately aligns with the climatic-ecological breakdown we are experiencing today.41

An Ecological Subsidiarity?

I have outlined a deeply impractical diagnosis, drawing from — but by no means doing justice to — the nuances of environmental-historical contingency. The natural extension of my conclusion-less argument is that the climatic and ecological crises we face are unarrestable — that they may well be part and parcel of the human condition. This is not what I want to get across, not least because the latter assertion is wrong. Instead, my intention is to simply expose the nature of human spatiotemporal dominance, and how that dominance has stripped ecosystems and their constituents of the agency to self-determine ecological outcomes. To arrest the crises we are all experiencing and will continue to experience, the restoration of this agency must be focussed on.

I am also arguing for a form of rhetorical temperance. Equally damning diagnoses are often made, with magical solutions thereto following in quick succession. Whether those solutions align with rights of nature or ecological economics, I feel that their potential weaknesses are not aired in public discourse enough — that is not to say that they should not be tested and pursued in absolute; just that they should be communicated ingenuously.42 I do not feel it to be appropriate to present solutions for the sake of it. My preference is to piece apart the problems they should address, and subsequently outline the shape solutions may take.

And the shape in question is that of ecological subsidiarity.43 Subsidiarity as a concept is well-established, referring to the idea that the responsibility and agency for addressing specific problems should be delegated to the lowest management level (best-)equipped to address them — typically expressing itself in a distributed form of governance like the European Union. Matters like international trade are managed at the highest level, by the European Commission. Matters like the collection of one’s bins are managed at the lowest level, by municipalities. Related matters like waste management are dictated at the highest level but implemented nationally, to be enforced through national legislative efforts.44 Our biosphere — by amalgamating and distributing local ecological knowledge in accordance with ecosystem actors’ wants and needs — operates in an unconsciously subsidiary manner.

A grasslands environment, say, is maintained by the interrelation of grazers like bison or buffalo; shortgrasses and longgrasses that enrich the soil to differing degrees; fungi that distribute nutrients between flora; the rains which bring literal and figurative hydration; and the sun, which acts as the source of all energy. Bison’s hooves aerate compacted earth whilst their selective grazing prevents any single grass species from achieving dominance. Prairie dogs alter landscapes through their extensive burrow systems, creating microhabitats that collect moisture and provide shelter for smaller creatures. Predators like wolves and coyotes regulate herbivore populations, their hunting patterns shaping the movement and behaviour of prey species across the grassland mosaic. Fire, too, sweeps across grasslands periodically, clearing accumulated thatch and returning nutrients to the soil whilst stimulating new growth. Each actor, then, operates according to their own individual knowledge and the environments they recursively interact with.45

In the oceans, phytoplankton bloom in response to upwelling currents that bring nutrients from the deep, their photosynthesis forming the foundation of marine food chains whilst simultaneously producing much of the oxygen we breathe. Krill swarm in massive aggregations, following these phytoplankton blooms and in turn attracting cetaceans whose migrations span entire ocean basins. Deep-sea hydrothermal vents create oases of life in the abyssal darkness, their chemosynthetic bacteria converting sulphur compounds into energy and supporting communities of tube worms, crabs, and fish. Ocean currents act as massive conveyor belts, redistributing heat from tropical to polar regions whilst carrying larvae, nutrients, and dissolved gases across continents. And coral reefs serve as underwater cities, their calcium carbonate structures built over millennia providing habitat for countless species whilst protecting coastlines from erosive forces. Actors in this way fill their own niches, spatiotemporally bounded in the immediate; a bounding we have taken advantage of through our escape therefrom.

If it sounds like I am describing — or rather defining — ecology, it is because I am. Ecology is by its very nature subsidiary, and subsidiarity is by its very nature ecological. Ecological subsidiarity is in a sense, then, a sort of needless, verbose, repetition — a repetition we must bear in mind when attempting to arrest the crises we face.

What does ecological subsidiarity look like in practice? It is hard to say.46 It likely involves some yielding of our spatiotemporal dominance — a yielding of that which allows us to excessively impose. Whether this entails an epistemological-ontological revolution that justifies the prerequisite selflessness therefor, recognising the mismatch between our physical ability to impose and our mental ability to perceive that imposition, or a forced climatically-imposed retreat, is equally hard to say. But without fundamental reform, or without revolution, non-humanity may be forced into (new) systems whose inherently incongruous spatiotemporal scales will continue to predetermine, and potentially worsen, poor climatic-ecological outcomes.

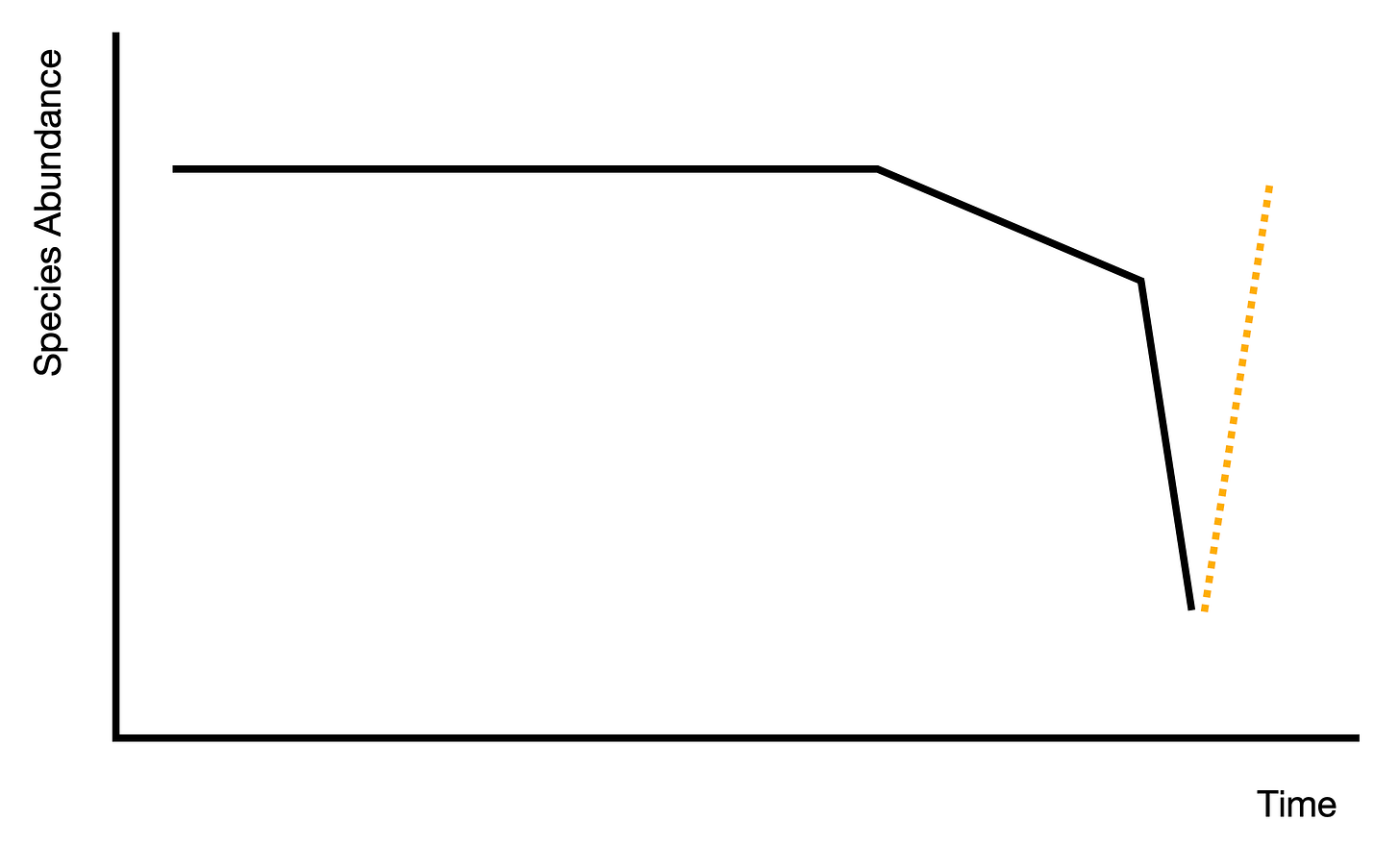

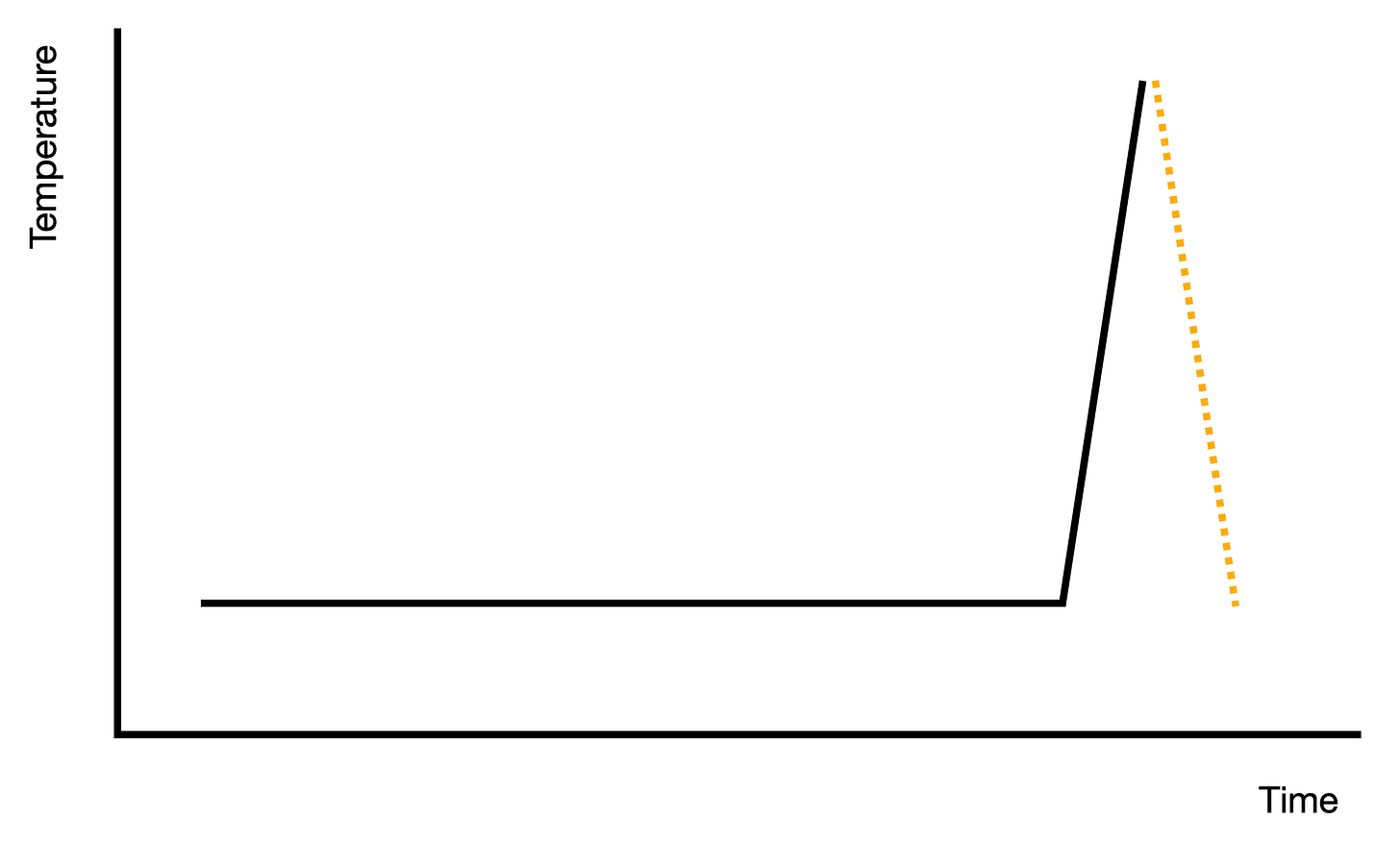

This forms the shape of, not the prescription for, a solution. Being realistic about one’s metrics of success, here, matters — should the ultimate aim be a deep ecological purge of human influence or a human-inclined legally-politically-economically-enforced balance? Whatever it may be, reversing the full extent of environmental-historical decline is a false expectation from the outset, as this decline maps our increased spatiotemporal dominance.

Whether getting a few increments along that dotted yellow line or following it in entirety is the aim, one must be rhetorically honest. Falling into the Edenic trap of identifying a single source of crisis and subsequently deciding that a single solution or set of solutions may bring us back to that point is not constructive. Nor, though, is a hopeful, overly-optimistic incrementalism that may not take us very far; or that optimism’s cousin: the boosting of half-baked solutions that come laden with impracticalities and malincentives.

Regardless, one can conclude that our present organisational-communicational arrangement is suboptimal. One can conclude — and agree — that our unilateral, deafening, and constant shouting is unkind and counterproductive. And one can also acknowledge that the extent of our spatiotemporal dominance, the enlarged (or inflamed?) size of our vocal chords, is problematic.

Or, perhaps, it is our using a megaphone that has led us to where we are today. Whatever the contents of the wavelengths travelling through that megaphone may be, they are unduly amplified, their amplitude unduly increased. It is high time to listen, to place to one side that megaphone; not to silence ourselves, and if it is in fact our vocal chords and not a megaphone that bestow upon us our ability to shout, not to rip out our vocal chords. We are needlessly in conflict with the natural world. Much like in a disagreement between two human actors, our shouting at the collective of non-human actors does both them and us little good — it simply degrades our relationship further; breaking down any semblance of trust and goodwill that may have existed — and could ever exist. And given the emitter of the sound can deafen themselves just as much as the receiver, perhaps we should quieten down instead of covering our ears.

For the first claim, evidence is pointing towards climatic shifts being paramount in megafaunal extinctions — but human influence nonetheless played a role. For the third claim, refer to Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis’s Commerce by a Frozen Sea and Andrew Isenberg’s The Destruction of the Bison as examples.

There is an inherent overlap with ontological approaches. For my purposes, I am treating the two similarly — given they both fundamentally describe a change in the perceived relationship with the natural world.

Carolyn Merchant’s work is a good starting point for further reading on this.

Epistemologies can, but by no means must, predetermine the range of possible organisational outcomes. The ways organisational frameworks are implemented can, too, influence the ways epistemologies change over time.

My use of the term technology is broad. I am not necessarily referring to constructed technology alone but rather a broad set of adopted or created ‘tools’ that compress space and time: think guns, horses, cars, fibre-optic cables, writing, and pickaxes. Organisational frameworks can themselves alter space and time depending on the nature of their resource allocation, but technologies underpin compression.

It is worth explicitly noting the contingency of technologies’ development and adoption. The extent of technologically-induced spatiotemporal compression we experience today is not an inevitability, and it would be deeply teleological to assume so. Tanker ships are not the natural extension of dugout canoes; nor are skyscrapers the natural extension of neolithic stone structures.

It is also worth noting the idea of the multipolar trap here. Whether or not one human community develops or adopts a technology, the technology’s development or adoption is made more likely by the fact that another community doing so would result in their (pre)dominance. A competitive dynamic, then, follows. For more on this, see Lorenzo Marsili’s work relating to inter-state competition.

Some have argued that our use of technology is part of the human condition. See Benjamin Bratton’s writings for more on this. I disagree with the teleological dynamics of this argument, informed by my academic work on the contingency of North American indigenous communities’ adoption of particular technologies, like the horse and ice pick. These, though, are sensitive historical debates, and my intention here is to tap into them — to use them as a contextualising tool — rather than delve into their nuance in full.

One other point that makes human actors relatively unique is the extent of their social learning. This refers to the ways information is distributed, shared, learned, and taught extra-evolutionarily — in a way that bypasses the relative slow-burn of evolution with the fast pace of human cultural change. For more on this, see here.

Defining human bounds, and making a judgement as to whether the use of an exogenous (or endogenous) spatiotemporal compressor is ‘ecological’ or not, is not possible in the absolute. Ecosystem actors are only discrete insofar that their use of these compressors is not deterministic. See previous footnotes for more on this.

The differing scales of actors’ interconnections should be mentioned, taking place at macro- and micro-scales. Whether it be the bacteria that inhabit our and other bodies and microbiomes or the nutritional cooperation of trees across entire forests, neatly delineating bounds is not possible.

To be clear, I am not making a value judgement as to whether humanity’s spatiotemporal dominance is right or wrong.

It is worth noting my exclusion of cultural frameworks, which align more closely to societal epistemologies. I do this as a matter of (un)familiarity, not as a judgement of their relevance.

Think of these as gravitational weights that can morph the ways they are interacted with in their interest.

This is hardly an exhaustive list.

The extent and scale of this management is an environmental-historical anomaly, much like the extent and scale of our climatic-ecological exploitation.

Before I go on, it is worth noting explicitly that the reason I separate legal, political, and economic frameworks is to align with the sets of solutions that are typically proposed as a counter to present climatic-ecological crises — like rights of nature, ecological democracy, or natural capital frameworks. They are of course in practice interlinked and interdependent. It is also worth noting that I strawman, heavily. In my critique of rights of nature, for example, I presume their full application (i.e. the assignation of legal personhood to all biotic actors), when in actual fact the field is a diverse set of legal approaches that can include the granting of rights to rivers or other specific waterbodies, the granting of rights to ecosystems as a whole, or the granting of rights to ants and termites. Rights and personhood are not necessarily interchangeable too. The same simplification applies to my discussion of economic solutions to our crises — nuance abounds, but I do not wish to write a book-length essay containing it all. My strawmanning, though, has a purpose: to support the precisionist narrowing of whatever solutions may be posited, and to expose those solutions’ more fundamental weaknesses in how they attempt to regulate human-non-human relationships.

To mitigate: they partly exist to moderate and arbitrate. This is not their sole purpose. Legal systems being essentially social constructs, they assist in the creation and regulation of social norms.

Although that mixed success is not necessarily down to regulatory-statutory approaches’ intrinsic shortcomings, but rather these approaches’ watering down and weakening (and their lack of resourcing).

Christopher Stone was of course the first to formally point this out. Thomas Berry’s and Cormac Cullinan’s works are other, later, notable additions.

Personhood partly embodies the dualistic logic that led to the imaginative separation between the human and non-human. In that sense, it is hard to endorse from the outset.

For more on non-human integration into human political systems, see Joana Castro Pereira and André Saramago’s Non-Human Nature in World Politics, particularly Anthony Burke and Stefanie Fishel’s Across Species and Borders: Political Representation, Ecological Democracy and the Non-Human.

For more on this, see Eva Meijer’s When Animals Speak.

For a thorough survey of these practical concerns, see Noah Sachs’s A Wrong Turn with the Rights of Nature Movement.

To mitigate this slightly: we do allocate legal resources in line with statutory animal welfare obligations — but this aligns more with our treatment of animals as objects, as property to be protected. A second mitigation: relation is not fixed and may well improve.

This is particularly considering that assumptions are routinely made on the underlying thought processes underpinning human misdeeds.

Biospherical sovereignty, wherein sovereignty is attained through universal selfless agreement, is the alternative — but as long as humanity maintains a spatiotemporal monopoly and refuses to cede it, that universality is an impossibility.

This decoding falls into a broader set of arguments that posit technology’s revolutionary potential to monitor and act on non-human actors’ wants and needs. I believe this to be a hubristic techno-utopian pipe dream that fails to account for the sheer size and diversity of ecosystems and the number of actors — known and unknown — that they consist of.

To mitigate this slightly: it is not that simple. One can envision a scenario wherein human interests are cornered by the manifold interests of non-human counterparts, and human rights are themselves contravened as a result. Other scholars have pointed this out aplenty, but only successive case law is likely to prove assuage-ive. See the next paragraphs for more on this.

This point is the result of serious strawmanning. To my knowledge, no serious rights of nature scholarship advocates for the management of non-human-non-human relations.

To be clear, this is not necessarily the case. Statute books and principles are not cast-iron structures — rather more flexible aluminium alloys with lower melting points. Judges and juries may wish to interpret and re-interpret them as they wish — fitting into broader sociocultural rhetoric and shifting attitudes. For more on this, see James Boyd White’s Law as Rhetoric, Rhetoric as Law: The Arts of Cultural and Communal Life. Relative to ecology, though, legal systems are less dynamic, unduly reinforcing vested interests and in some instances acting as barriers to change.

In the legally-unarbitrated long-run, a mangrove would be the result.

To mitigate this: legal systems do not presume total knowledge — they presume knowledge or understanding of matters beyond reasonable doubt.

Were personhood and a corresponding political voice to be assigned to non-human actors, it could be envisioned that this voice, in the course of normal life and death, be passed onto progeny. With this voice could come continued personhood. But without any leverage to guarantee this voice — no ability to rise up, peacefully or violently — its maintenance is hard to imagine. Think here of the successive successful battles for the right to vote by marginalised human groups, whether non-landowners, people of colour, or women.

A comparison can be drawn to wage labour or the valuing of human intellectual capital. The value of labour or intellectual capital does not dehumanise the labourer or capital-holder — but this is only because their humanity is legally-democratically guaranteed. More on this later.

For more on this, see Mark Sagoff’s The Economy of the Earth. With thanks to Amelia Holmes for recommending this great book!

Separately, clarifying the form optimisation takes and can take is important. Markets are natural optimisers — and this can be a good thing. If (theoretically) valued and measured appropriately, the quantity of “nature”, however defined or delimited, would almost certainly increase. Assuming a perfect methodology or a set of perfect methodologies, all would be fine and good. But this ignores the political economy, and ignores the nature of nature as an economic provision in the first instance. Private actors’ interests are incongruous with the natural world’s interests — and this incongruity would reveal itself over time once those actors capture market share and seek to prioritise their bottom lines (a perfect regulatory framework could mitigate this, but that is far from guaranteed — let alone achievable). And the natural world is better provided as a public good regardless, which I have discussed at length here and here. Focussing on the construction of elaborate private markets misses these points, and sucks oxygen out of the rhetorical and political space which can accommodate solutioneering.

In principle, particularly when considering the timing of representational values’ allocation. If exploitative economic value were to, for example, be applied first, the subsequent application of legal and political values would be more difficult. As legal and political value would increase economic value, the actors involved in that values’ trade would be opposed to their introduction and exercise their power as such. If an epistemological revolution that would redefine our relationship with the natural world along legal-political lines was the aim, the initial introduction of economic representational value would be problematic too — precisely because it would embed the natural world as an instrumentalised object into our sociocultural economically-influenced fabric.

This is true whether that value (in the cost sense) stands at zero — which in most instances is the case today — or at a value greater than zero. An economic value is an economic value. Without extra-economic protections, actors are little more than tradable, exploitable, commodities. And in any case, that value has to be negative in that its use has to impose a cost on the user — rather than a positive value where its use confers a benefit upon the user.

Having said that, there is a clear difference in how we treat different kinds of valued actors, and how we treat the inanimate natural world in particular. The flood-regulating value that a wetland provides is different to the provisioning value that livestock or a wild animal may provide.

Here I am referring to it as an economic term, rather than in the sense of universal consciousness.

Taken from Leon Trotsky’s The Soviet Economy in Danger.

Taken from Friedrich Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society, 521-522.

ibid, 523-524.

In my organisational diagnosis of decline, I wish to partly set myself apart from Murray Bookchin’s The Ecology of Freedom. His argument is that social and ecological ills stem from the historically-built-up hierarchy of societal structures. For me it is less about the dynamics of the structures in question and more about the fact that those structures exist — and sit atop of ecology — in the first place.

This is also not to say that their weaknesses are not discussed at all. Academic circles can be pretty, and fairly, critical.

I am here aligning myself with Nils Gilman and Jonathan Blake’s arguments in their Children of a Modest Star.

The EU’s present disaggregated military arrangements are demonstrating the weaknesses of subsidiarising that which should not be subsidiary.

It is worth noting, however far down in this piece that note may come, that my lack of differentiation between animate and inanimate matter — or rather biotic and abiotic actors — stems purely from my desire to dodge defining that differentiation; a defining that I don’t feel is necessary for the purposes of the arguments made here.

This difficulty should not result in the idea’s dismissal. As Elinor Ostrom argued in her Decentralisation and Development: The New Panacea, new systems of governance should not be dismissed out of hand due to their perceived complexity, or their (potential) mess and chaos.

I like how comfortable you are with ambiguity and chaos, yet still discern patterns.

Thanks for sharing.