The $1.7 Trillion Elephant: Academia Has Yet to Buy Into the Private Nature Finance Story

I was attending an event at London Zoo a few weeks back, held in collaboration between the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, Finance Earth, and the Zoological Society of London. We were marking the Coalition for Private Investment in Conservation’s Semi-Annual Member Meeting, with discussions centring on private nature finance initiatives in the marine sphere — given the UN Ocean Conference was taking place at the time.

Whilst having considered this beforehand, what hit me at the zoo, of all places, was the sheer overemphasis on private finance as a solution to the ecological challenges we face today. This is hardly new, with scholars — and even the World Bank — having highlighted it aplenty. I was, naturally, self-selecting; attending an event explicitly discussing the (supposedly crucial) role private finance has to play in nature conservation and restoration. But I felt this overemphasis had been replicated at previous events and conferences I’ve attended — and replicated in recent policy movements. At Rewilding Futures in January of this year, a two-day conference which took place in Cambridge, the few explicitly finance-focussed discussions tended towards private finance: with an emphasis on philanthropy, charismatic carbon, BNG, and the ever-nascent — never quite ascendant — biodiversity credit market. The UK Government recently, too, launched a consultation on expanding the role of private finance in nature recovery; perhaps a reflection of its recent second-guessing of ELMS-centred subsidy regimes — although oddly misaligned with its earlier second-guessing of BNG.

In conversation with a representative of Finance Earth, the incongruence between the need for expanded finance for nature recovery and the mass state-sponsored subsidisation of biodiversity-harming activities came to the fore.1 The finance gap for nature recovery is estimated to stand at up to $800 billion a year, while subsidies for biodiversity-harming activities are estimated by IPBES to be roughly $1.7 trillion a year. While that finance gap doesn’t necessarily need to be filled by private finance alone, emphasis has tended to fall thereon in the context of faltering government action — governments’ continued failure to meet their own $200 billion a year Kunming-Montreal target for biodiversity conservation and restoration, which conveniently highlights the mobilisation of all financing flows, is a case in point. Equally, the incongruence between the relative complexity of nascent private nature finance initiatives and the relative simplicity of government-funded public good-centric nature financing became evident.

So I thought it would be prudent to measure whether the (over)emphasis on private nature finance that I’ve anecdotally experienced is present in academic literature discussing these matters. Is the disproportionate emphasis on private over public finance reflected in the subject and thrust of academic research? And is the importance of reducing or removing biodiversity-harming subsidies outright understated?

My methodology was as follows: I first used Web of Science (WoS) to identify journal articles, books, and other publications that discussed biodiversity-related finance. My search query for this captured all publications that mentioned both biodiversity and financing of some kind. I limited results to full calendar years, stretching from 2000 to 2024, and filtered for English-language outputs too — capturing a range of data that I would be able to spot-check.

WoS Search Query

TS=(

("biodiversity" OR "biological diversity")

AND

("financ*")

)

AND PY=2000-2024

AND LA=English

I then downloaded the identifying information of each publication — like its title, author(s), journal, and abstract — as a series of text files and loaded them into a CSV using a basic Python script. My thinking here was that a publication’s abstract would contain enough information on its general thrust and position. Hardly exhaustive, but enough — particularly given my next step was to utilise another Python script and my Google Gemini API key to use Gemini 1.5 Pro to analyse each abstract. Downloading the entire text of each publication would not have been feasible using WoS’s aggregator in the first instance, and analysing the entire text of each publication in the second instance using Gemini would have been rather expensive: 3,345 publications were identified, with the total word count amounting to 1,120,299 for the data I downloaded alone.

My aim here was to measure a few things: whether a publication discusses private and/or public biodiversity financing; what its sentiment of this form of financing was (positive, negative, or neutral); and what its confidence on these points was too. I additionally wanted to ascertain these same attributes for discussion of harmful subsidies in isolation.

My prompts to measure these things were as follows. You’ll notice that I requested Gemini to assign a confidence score, write a rationale for each of its decisions, and print the keywords identified. The confidence score, in this case, was not a strict statistical test — it was simply based on Gemini’s impressions of the text at hand. Full disclosure: I utilised a mix of LLMs to assist in writing these prompts and the full script.

Private

You are a meticulous research assistant.

Read the journal abstract below. Decide whether it explicitly discusses

PRIVATE-sector biodiversity finance. Using your judgement, recognise *any* of these and/or similar themes:

• corporate investment / corporate social responsibility

• impact investing, blended finance, private capital

• biodiversity offsets or credits, carbon credits, voluntary carbon market

• green or sustainability-linked bonds

• philanthropy, private donations, endowments

• project developers or public–private partnerships with a finance component

If the abstract *does* discuss private-sector finance, classify the overall tone:

• "positive" = portrays it favourably or as beneficial.

• "negative" = criticises it or highlights harms/risks.

• "neutral" = purely descriptive, balanced or ambiguous.

If no private-sector finance is present, answer "false" and set

"private_sector_sentiment": null.

Return ONLY a valid JSON object – no comments, no extra text:

{{

"discusses_private_sector": false,

"private_sector_sentiment": null,

"private_sector_keywords_found": [],

"rationale": "",

"confidence_score": 0.0

}}

Public

You are a meticulous research assistant.

Read the journal abstract below. Decide whether it explicitly discusses

PUBLIC-sector biodiversity finance. Using your judgement, recognise *any* of these and/or similar themes:

• government budgets or expenditure for conservation

• fiscal incentives, earmarked taxation, biodiversity levies

• direct public subsidies

• international aid / ODA / multilateral funds

• intergovernmental transfers; national biodiversity-finance plans

If the abstract *does* discuss public-sector finance, classify the overall tone:

• "positive" = portrays it favourably or as beneficial.

• "negative" = criticises it or highlights harms/risks.

• "neutral" = purely descriptive, balanced or ambiguous.

If no public-sector finance is present, answer "false" and set

"public_sector_sentiment": null.

Return ONLY a valid JSON object:

{{

"discusses_public_sector": false,

"public_sector_sentiment": null,

"public_sector_keywords_found": [],

"rationale": "",

"confidence_score": 0.0

}}

Harmful Subsidies

You are a meticulous research assistant.

Read the abstract below. Using your judgement, detect *harmful* biodiversity-negative public subsidies or perverse incentives (e.g. fossil-fuel, agriculture, fisheries, mining) and/or similar themes in the abstract.

Sentiment rules: "negative" = condemns or proposes removal,

"positive" = supports, "neutral" = purely descriptive.

Return ONLY this JSON:

{{

"mentions_harmful_subsidies": false,

"harmful_subsidies_sentiment": null,

"harmful_subsidy_keywords_found": [],

"rationale": "",

"confidence_score": 0.0

}}

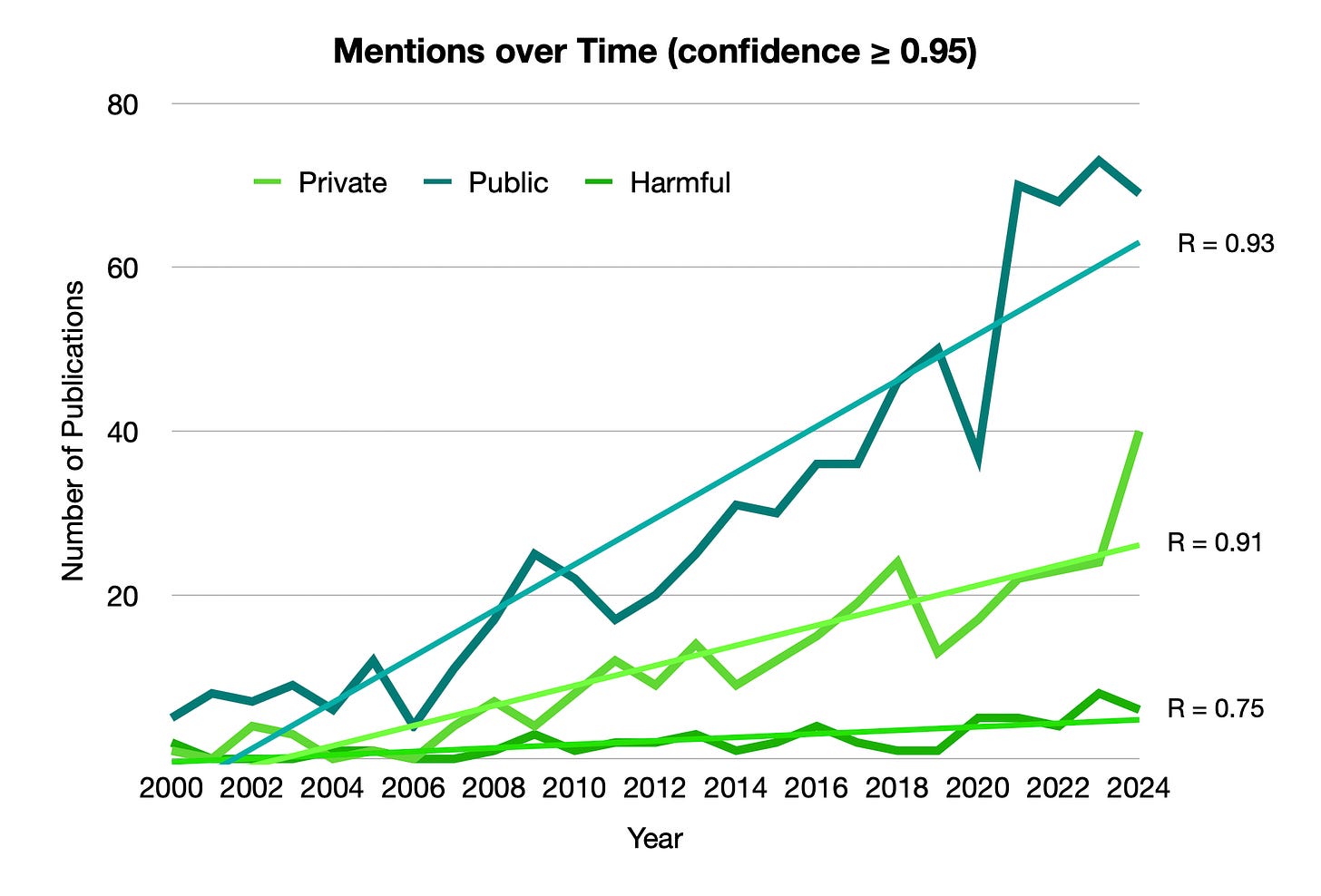

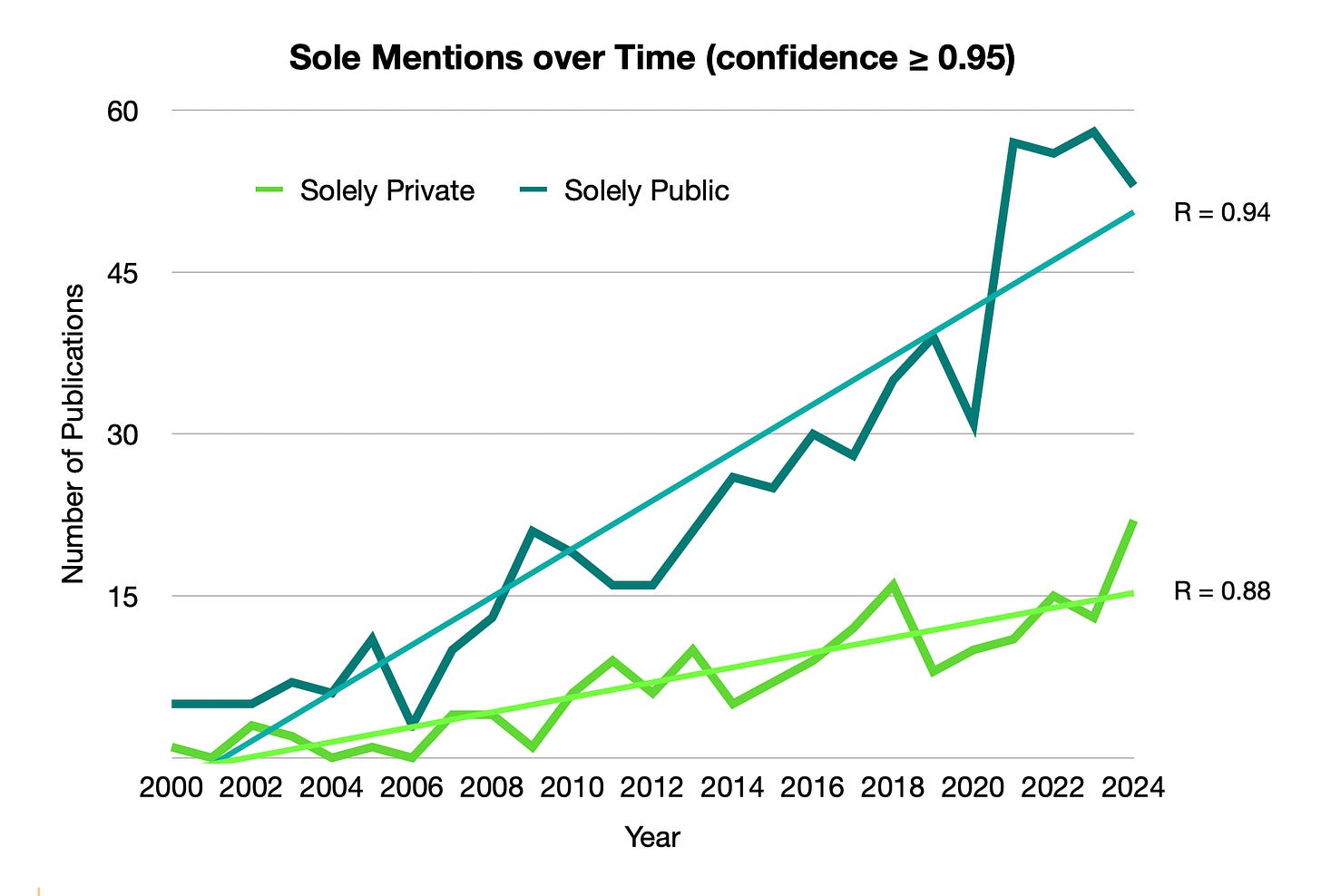

Now to the results. My initial hypothesis, mirroring my anecdotal experience, was that discussion of private finance might be disproportionate to the need to scale up public finance and scale down public malfinance. This was thoroughly disproven.2 For every publication discussing solely private interventions in nature recovery over the past five years, there were a corresponding four publications discussing public interventions.

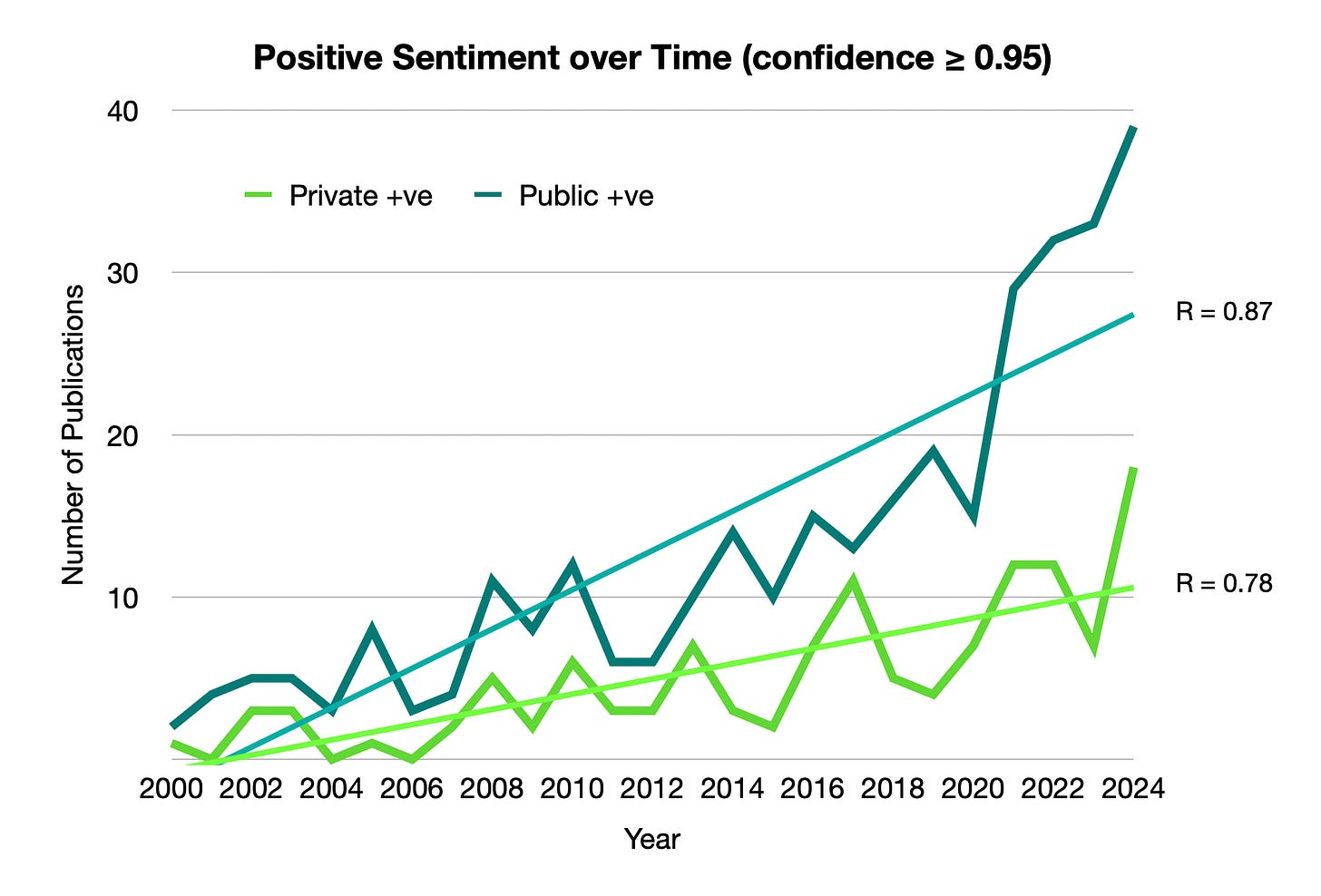

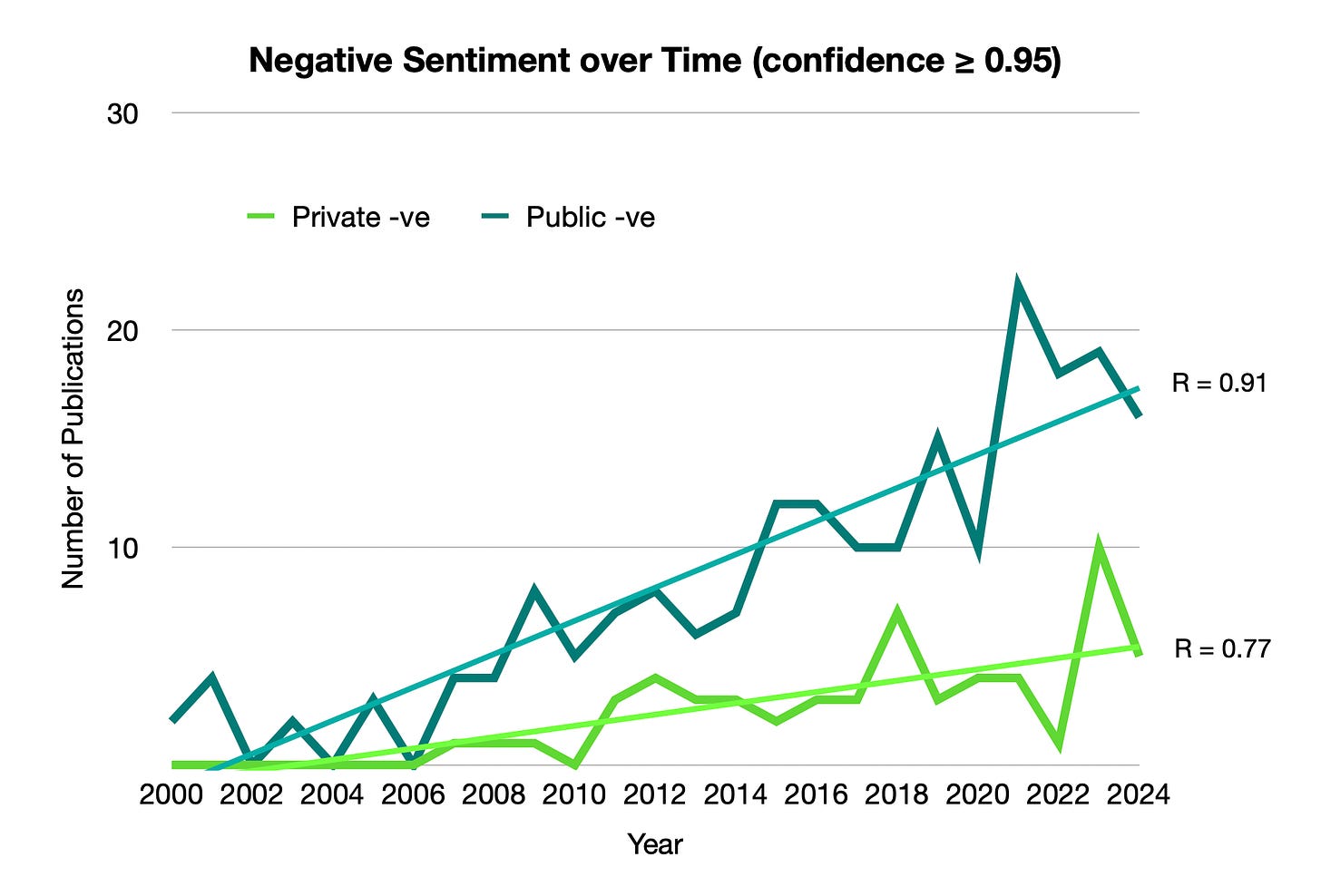

It is clear that mentions of both private and public interventions increased substantially over the years — the jump in mentions of public interventions in 2021, for reference, is mostly correlated with Kunming-Montreal. I have excluded sole mentions of harmful subsidies given their strong overlap with public interventions. I have also excluded their mentions from the sentiments diagrams as they were steadily wholly negative.

The professional discourse I have been surrounded by is clearly misaligned with academic discourse. Perhaps this is because the incentives of each are themselves misaligned — with private finance wishing to justify its intervention, and academia being relatively independent from the influences this dynamic would bring about.3 Regardless, the importance of public interventions highlighted in academic literature is evidently not reflected in government policy. Nature-friendly discretionary spending and subsidies are few and far between, and when existent are orders of magnitude smaller than their nature-harming counterparts — which continue to fuel destructive, land-inefficient, polluting activities. And the $1.7 trillion in subsidies highlighted by IPBES do not stand alone: they incentivise a further $5.3 trillion in biodiversity-harming private financial flows.4

It is in this vein that the limited academic discussion of harmful subsidies makes sense: they are an easy problem to solve. Political barriers aside, they can simply be removed.5 One doesn’t have to create complex new regulatory frameworks or voluntary markets to funnel supposedly eager private capital into nature recovery. One, neither, has to expend the effort, nor the political and intellectual oxygen, needed therefor. The solutions are already out there — it seems, to me, ideological to insist on alternative pathways.6 Perhaps governments should take a greater cue from the ranks of academia.

For those who are interested, I would be happy to share my full script, alongside my raw data (WoS licensing-willing). There were, based on a spot-check of the data, a few false positives — although these were neither substantial nor substantive. The aim of this exercise was to uncover trends more than anything else — and in this regard Gemini was broadly right. Regardless, I would encourage all readers to not draw major conclusions from this small piece of research, particularly given I was analysing abstracts alone.

How would I take this thread further? I would look at specific journals like Ecological Economics; I would look at publications’ entire texts; I would control results by number of citations; I would look at a variety of publications outwith those listed on WoS, like Substack; I would manually sift results to a greater extent to ensure higher integrity; I would conduct equivalent sweeps of existing and prospective legislation and policy developments in differing jurisdictions; I would conduct equivalent sweeps of social media feeds of those involved in the sector; I would refine the prompts given to the LLM; and I would use a variety of LLMs to aggregate results.

With thanks to Goizeder Blanco-Zaitegi, Igor Álvarez Etxeberria, and José Moneva for their Biodiversity accounting and reporting: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis; Simona Cosma, Giuseppe Rimo, and Stefano Cosma for their Conservation finance: What are we not doing? A review and research agenda; and Yasin Guer, Lukas Mueller, and Dirk Schiereck for their Biodiversity: A Bibliometric Analysis of Accounting, Economics, and Finance Journals, from whom I have taken inspiration for this research.

Thanks for your interest — any feedback, questions, and/or comments are warmly welcomed!

Subsidisation and incentivisation, here, are interchangeable.

This partly replicates the results of Cosma et al., who concluded that there is a ‘substantial lack of interest of scholars in the banking and finance sector for issues concerning the protection of biodiversity’.

In fact, some of the most vociferous critiques of private finance’s involvement in nature conservation and restoration come from academia.

It is worth noting, though, that biodiversity-harming subsidies are not necessarily swappable like-for-like with nature recovery-centred private or public finance.

This being a big aside, particularly considering the broader political economy.

That is not to say that public finance — or however we label state-financed intervention — is a panacea. I have criticised this position too. It is just that in the paradigm we inhabit at present, it seems to be a more efficacious, and timeous, solution.