The Enshittification of Nature and the Limits of State Intervention

Preface

This essay has been sitting in my out-tray for some time. My intention with it was to critique existing approaches to the finance gap for nature conservation and restoration — it turned into a broader criticism of private, market-centric, and public, state-centric, (perceived) solutions.

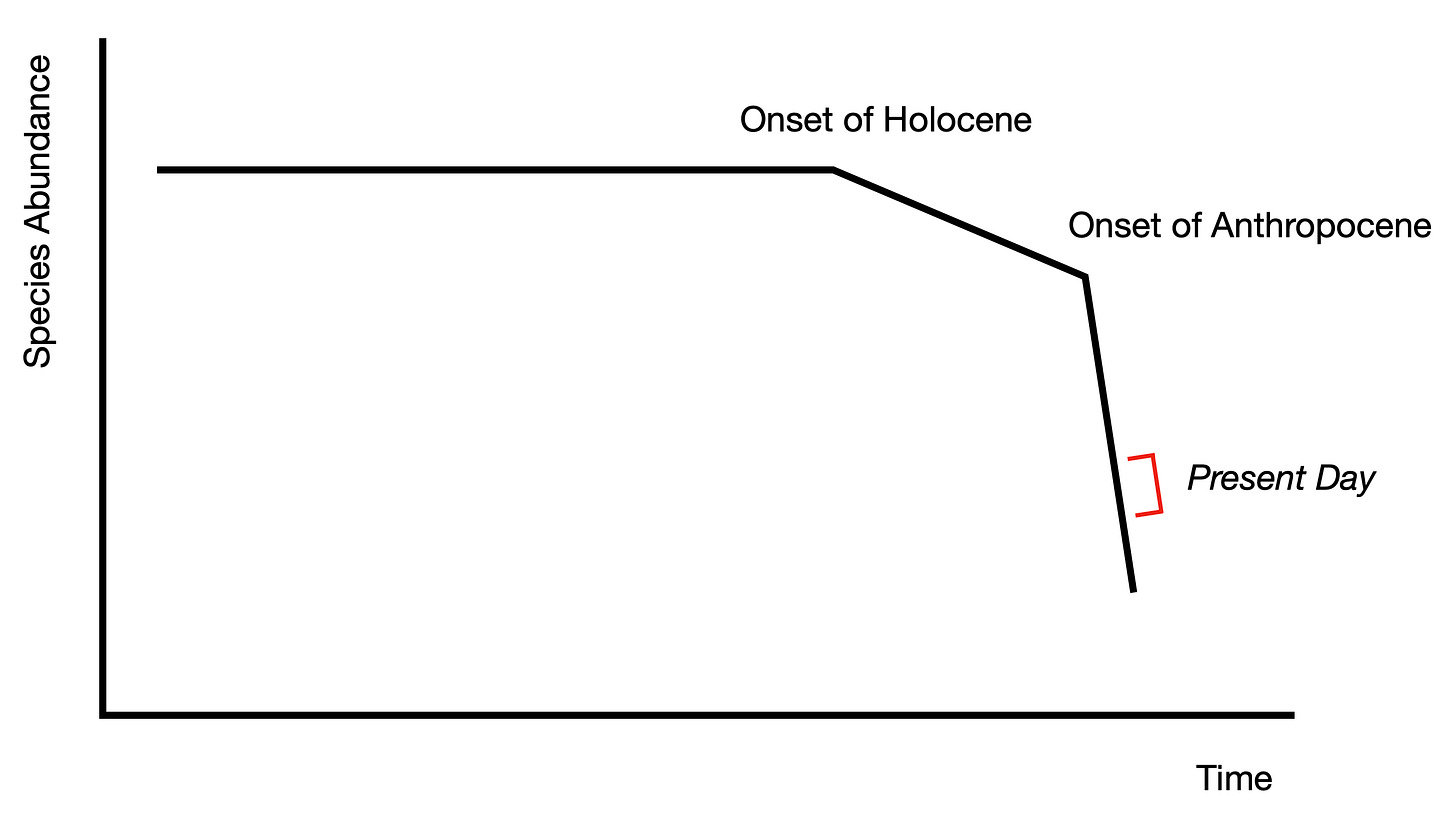

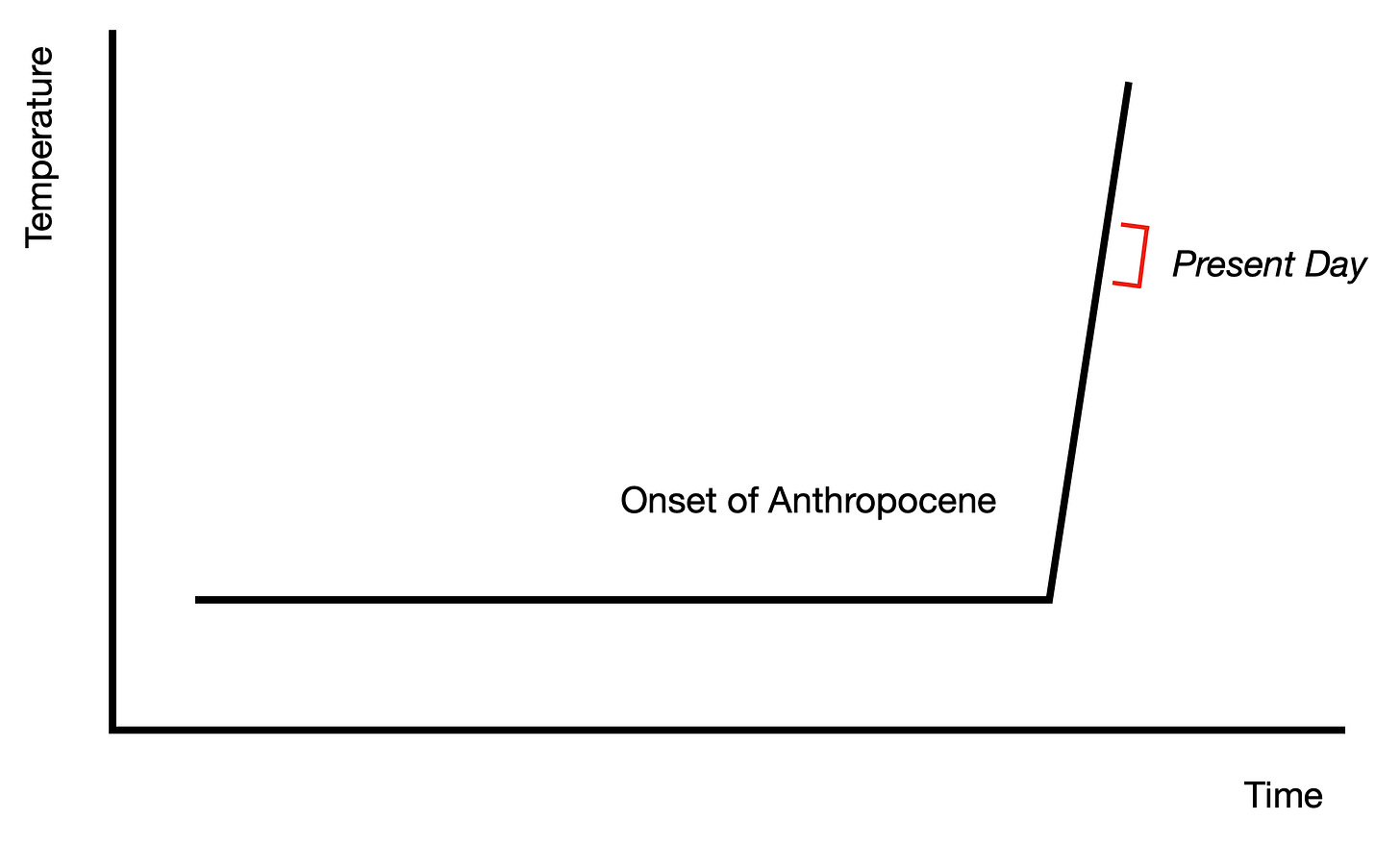

I go hard on these supposed solutions, and the strength of my critique should be historically contextualised. The extent of human-induced ecological decline and climatic crisis is stark.

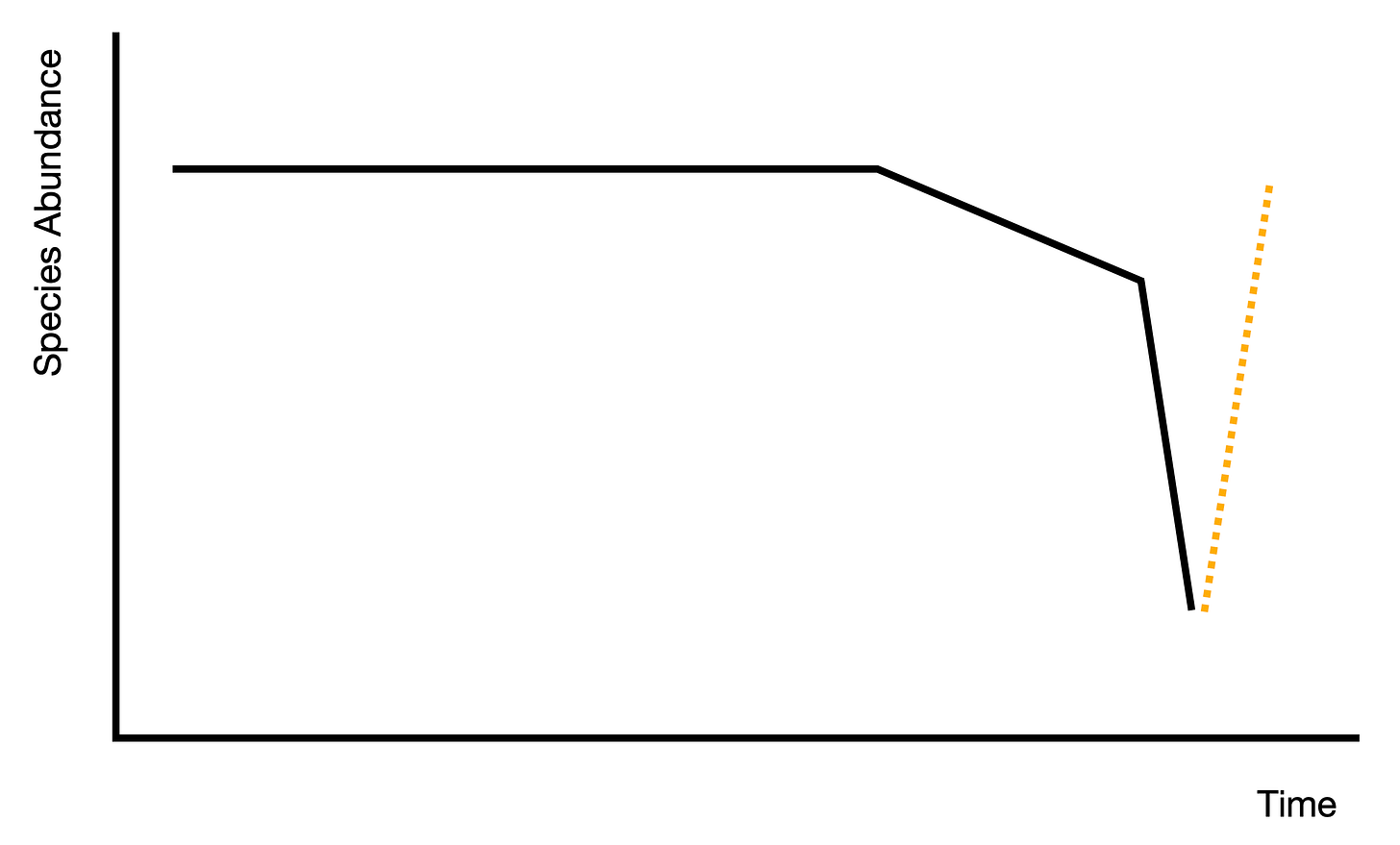

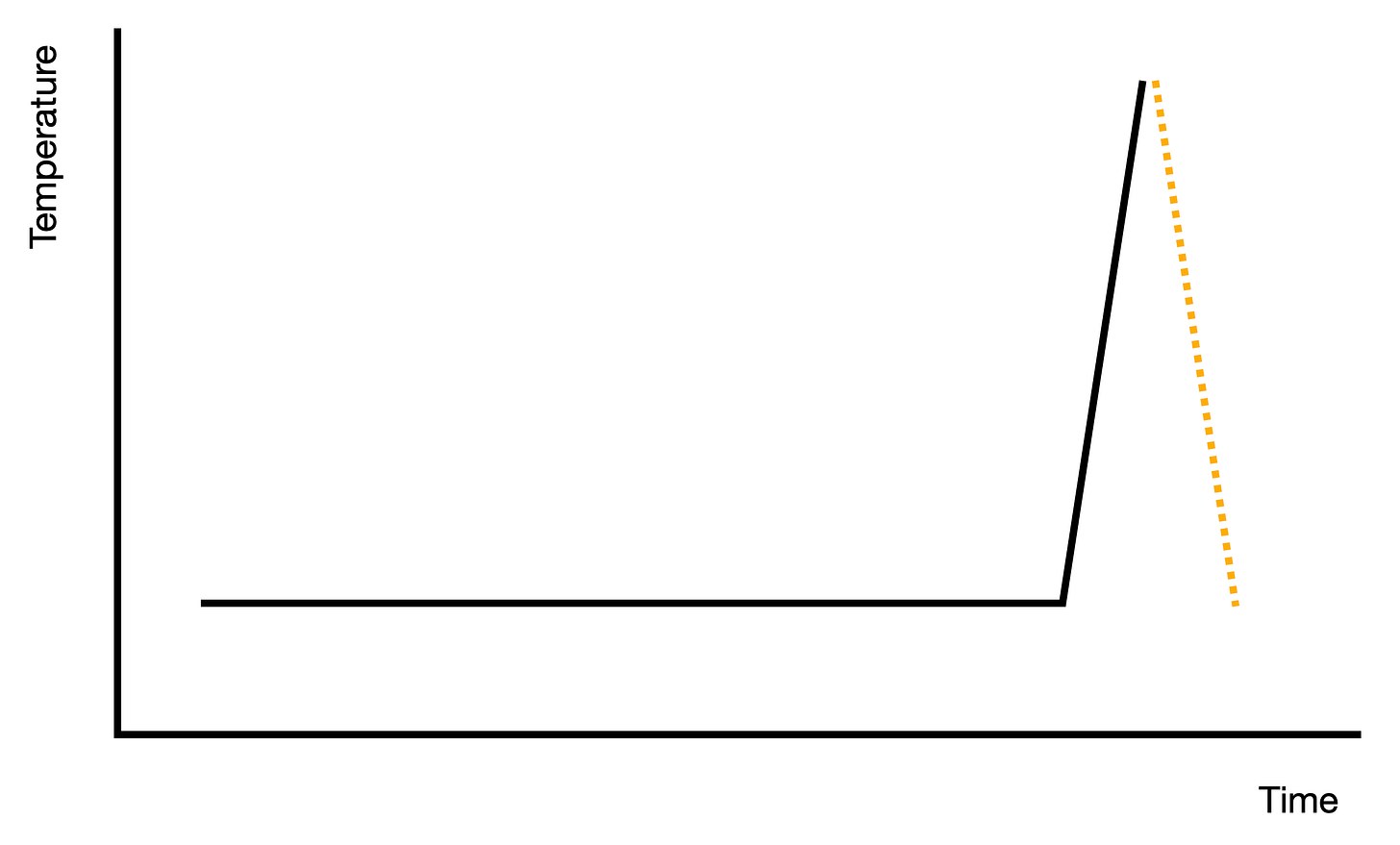

These diagrams are rough, and their timelines are deliberately vague given the difficulties of approximating these onsets. Their purpose, though, is to illustrate the temporal impotence of existing human economic structures.

The solutions discussed in this essay occupy a profoundly short period of human, and planetary, histories. They are the products of an amalgam of context-dependent, contingent, developments. Whether to explicitly link their previous rise and use to the ecological and climatic challenges we face today is another question — what must be kept in mind, though, is that their continued use is far from inevitable. When finding solutions to today’s problems, we cannot and must not focus on time horizons of twenty to thirty — or even one-hundred — years. We must think about the truly long-term, beyond potential living memories; about the systemic implications and second-order compounding effects the solutions we use now may reveal later. Are these solutions, importantly, capable of reversing the full extent of historical decline?1 Or are they more marginal, when viewed in sum? It is with this (somewhat impractical) frame of mind that I encourage you to read the below essay.

The Current State of Earth's Ecology

Were a cosmic visitor to descend from the skies to assess the health, vibrancy, and continued viability of our planet’s ecology, they would be astounded by its poor state. They would find an ecological dictatorship — a planet overrun by the desire of a single species subjugating all else. They would find that single species to be spectacularly short-sighted — continually making decisions that accord poorly with their continued vibrant longevity.2 And they would find decision-making structures that are impressively unsuited for making decisions that align therewith.

This cosmic visitor, had they paid the planet a visit every fifty thousand years or so, would be astounded by the sheer decline experienced by the inhabitants of its lands and seas: previously brimming with life — now emptied. They would observe a near-totalitarian dominion expressed through spatial dominance: the majority of habitable land converted for a single species’ usage; its superabundant oceans thinned to a trickle.

In short, our cosmic visitor would not look upon us kindly. Their concern, were it to be real rather than theoretical, is well-grounded. We, humanity, are masters of manipulation. We have razed ecologies and ecosystems in most instances of our existences: over the past 100,000 years, the biomass of wild mammals has decreased 85% — reflecting both our zealous hunting thereof and our later mass foray into animal agriculture. Today, only 4% of mammals live in the wild, while over the past fifty years alone total species abundance has decreased by more than 70%. Our totalising impacts on wild biomass are mirrored by — as our cosmic visitor observed astutely — our monopolisation of lands and seas. An area the size of the Americas is dedicated to animal agriculture; an area the size of China dedicated to arable agriculture.3 That not dedicated thereto, or to forestry, urban habitations, or recreational space, only remains so because we will it.

In what to us would seem to be touristic nescience, the visitor would then confusingly look upon our present position. Enraptured by pervasive and seemingly inevitable decision-making structures — dominated by exclusionary and short-sighted political, economic, and legal frameworks — they would be bewildered by our temporally and imaginatively narrow horizons; our sheer inability to arrest and reverse the ecological crises we have brought about.

This essay is split into four parts:

Economic Systems and Their Approaches to Ecological Crises

Marketisation — The Use of Market Mechanisms

Statism — The Use of Direct State Intervention

The Limits of Private Intervention

Enshittification — A Big Tech-ish Misalignment of Incentives

Implications — The Impacts of Misaligned Incentives

The Limits of State Intervention

Frailty — The Temporary and Narrow Nature of Political Decisions

Centralisation and Benevolence — The Dangers of Centralised Decision-Making and Assumptions of Benevolence

Our Imaginative Deficiencies — Charting a Way Forward

Please skip ahead or switch between them as needed!

Economic Systems and Their Approaches to Ecological Crises

Our economic frameworks, in particular, would be a cause for concern. Those structures — or rather the multifarious ways of managing and organising human economic systems — arise from one primary need: the need for human actors to communicate their needs and wants with one another, across space and time, and for those needs and wants to be met efficiently. They arise from the matching of one human actor’s desires with another human actor’s ability and willingness to meet those desires.4 Economic systems are ultimately systems of exchange based on the principle of infinite wants and finite resources — a near-physical fact that those systems’ varying structures try, and often struggle, to meet.

For the sake of dichotomising and reductive simplicity, there are two systems proffered to resolve the (soon-to-be) hellscape that our cosmic visitor observes: one with a preference for an amalgam of private, singular, actors acting in accordance with their own defined interests, and another with a preference for statism — wherein a unifying organisational body allocates resources according to agreed upon, whether democratically or otherwise, maxims. Singular actors’ own interests are primarily self-interested — they seek their own self-preservation and perpetuation, which at times align with the self-preservation and perpetuation of the economic and societal whole. Statist organisational bodies are, too, far from disinterested, acting according to their own set of incentives — primarily their constituents’ self-preservation.

How is this applicable to our cosmic visitor’s vision? A private solution, recognising the private human constituents that make up human economic systems, would emphasise each actor’s own internalisation of their externalities — the calculation and mitigation of their own impacts. Individuals, corporations, and other organisations would stand to be responsible for the harm they cause, and be responsible for that harm’s reversal. That is of course assuming that individual actors would be willing to actually do this. A statist solution, recognising that it is extraordinarily difficult to coordinate disparate human actors with disparate wants and needs, would emphasise societal, communal, calculation and mitigation of impacts. Both solutions, too, would fundamentally realise that the natural world is a basic form of capital that underlies human economic systems — through the provision of clean air, clean water, fertile soils, abundant seas, a regulated climate, and regulated weather.

Marketisation

Focussing on ecological impacts specifically, a private solution would entail a market of some kind.5 This market would assign value to the use or misuse of an ecological good. If a farmer or developer, say, wishes to convert a piece of land to primarily human use, that farmer or developer would pay a requisite fee to either discourage that conversion in the first place or to compensate for that conversion through restoration projects elsewhere. In practical terms, this sort of set-up exists for developers in some jurisdictions: Biodiversity Net Gain in England, biodiversity offset schemes at federal and state levels in Australia, and habitat-specific offset schemes at a federal level in the United States, to name a few.6 I won’t get into the weeds of how each specific scheme functions — what is important to note is that the state, in these instances, acts as an arbiter, a market-maker, by creating and regulating these markets in the first place.

Going beyond land conversion and development, a private addressal of human actors’ ecological impacts would involve each actor mitigating for every act that carries ecological baggage with it — which, essentially, is anything a human actor might occupy themselves with. If a company is to purchase a particular good, the production of which harms a set of species in a habitat or a habitat as a whole, that company must financially mitigate that impact by providing equivalent habitat elsewhere. The same would go for an individual wishing to do this — although it is unlikely for efforts to be duplicated (i.e. if a company has already mitigated their impacts, an individual purchasing goods from that company would not be inclined to double-up on that mitigation, given the costs involved in doing so).

And beyond offsets of this kind — essentially operating on compensatory, destructive, logics — private actors could equally acknowledge natural capital values in whatever decisions they make. Business and investment cases, or simple purchase decisions, could have recognition of and built-in leeways for natural capital reliance — think coupon payments on a grand scale, wherein the entire natural world is borrowed by us and interest must be paid thereon.

Now — a private addressal in all existing instances involves a state mandating those addressals through regulatory frameworks. This does not necessarily need to be the case. In theory, private actors could themselves recognise the value the natural world provides and integrate this into their economic decisions more broadly — think of this as an ecologically-inclined (truly) free market. But for the time being, state-regulated markets are all that exist. Private actors would be at pains to find reasons to place themselves at a short-term competitive disadvantage to their peers by incorporating a previously free piece of capital onto their balance sheets voluntarily.

Statism

Hence the inclination for greater statist influence predominates. The natural world is almost by definition a public good — its positive externalities are ample, it is under-provided by free markets, it is non-excludable, and it is non-rivalrous. Statist solutions are therefore well-suited for intervention, ensuring its continued health and adequate provision. They could, practically, take the form of wholesale provision — think here of the National Health Service in the UK, funded primarily by general taxation under the principle of being free at the point of use. Individuals, firms, and other actors — through taxed income, interest, and spending — fund healthcare’s public provision for public benefit. Instead of every private actor being responsible for their own individual healthcare, resources are effectively pooled to provide it efficiently and equitably. While healthcare isn’t necessarily considered a classical public good, other examples — like defence — are similarly applicable. A nation’s military can be seen as providing base-level prosperity by ensuring peace, and it is most efficiently and equitably provided for when funded collectively, catering to the interests of a general populace rather than specific individual private actors. The idea of direct statist intervention of this kind in the integrity of the natural world is not new. Matthew Kelly’s Nature State, for example, has examined it in the field of conservation.

Converse statist intervention takes place regularly through subsidy regimes — governments subsidising uneconomical activities they deem desirable. The most obvious target is agriculture, particularly in Europe. Under these regimes, the value of food security and food sovereignty is recognised, allowing domestic farmers to compete with more efficient, and thereby cheaper, imported produce. In the EU, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) at its most basic paid farmers on a per-area basis, prior to recent reforms. In England, CAP was replaced by an environmentally-inclined subsidy regime, ELMS: ranging from the incentivisation of smaller interventions like hedgerow planting to larger interventions like water redirection and flooding and even full land conversion, the latter being under the Landscape Recovery Scheme.7 Until recently and at present for the most part, though, subsidy regimes have disregarded and continue to disregard the natural world, incentivising land-inefficient and high-externality food production — including mining and forestry, $1.7 trillion a year is shelled out globally to support biodiversity-harming activities.8

With all of this in mind, both private and public solutions to the ecological crises we face are flawed. Both are overemphasised by sometimes warring parties, and both fail to take account of the bankruptcy of existing and prevailing economic and political schools of thought. Let’s examine them in turn.

The Limits of Private Intervention

Private solutions’ flaws are manifold, but depend on the degree of state intervention that leads to their arisal in the first place. Taking private solutions at face value and assuming private actors reach a level of enlightenment that takes into account their fundamental reliance on the natural world and leads them to act accordingly, they are deeply inefficient. The ecological crises that enwrap human and ecological communities are massive. They transcend individual actors, no matter how small or large they may be; no matter what literal or figurative footprints they may have. They transcend geographies and they transcend jurisdictions, and they occur at an interlinked scale that individual actors are unable to comprehend, keep track of, or often understand in the first place — an ecological equivalent of the local knowledge problem.9 Considering the natural world to be a public good, a face-value private solution is manifestly unable to provide it — this entails a short-termist prisoners’ dilemma of epic proportions. If one private actor avoids and mitigates but the other doesn’t, the avoider and mitigator loses out. If one private actor stays put and the other avoids and mitigates, then the other actor loses out.

And although the reasons for this are multifarious and diverse, public-ish goods that are and have been privately provided tend to underperform in broad-based and underlying equity. Utilities, water in particular, in Britain; healthcare in the United States; domestic and foreign security in less-stable nations with limited state capacity. Even relatively private goods, like housing — on a public-benefit basis — often perform better when supplied by the state: Singapore, a country where 80% of the populace lives in publicly-built, owned, and maintained housing is a good example of this.10

More relevantly to the immediate trajectory the financing of ecological recovery is taking, though, private solutions tend to follow a warped set of incentives by utilising tokenised, credit-like, units of nature. In existing regulated mechanisms like BNG in England, for example, developers are incentivised to in the first instance avoid having to be compelled to compensate land conversion. While this, in a way, is exactly the behaviour the legislation seeks to encourage — i.e. not developing if that development is not worth the associated compensation — it perversely leads developers to seek loopholes that circumvent the need therefor.11 In the second instance, and more importantly, and assuming developers travel down the harm mitigation hierarchy and opt for off-site BNG units ‘harvested’ by a habitat bank elsewhere, the provisioning and pricing of those units are what is optimised for — and this applies to non-statutory, voluntary, biodiversity credit markets too.12

This has two associated issues: the first is that the methodology of those units is far from perfect — this is a critique that can be applied to any methodology that measures biodiversity intactness and integrity. Each methodology (hopefully) considers the best available evidence at any one time and incorporates this accordingly. But given our ecosystemic knowledge is far from complete, creating standardised metrics that private economic actors construct their entire business models around is questionable. This applies no matter what the methodology used may be — whether basing itself off ecosystem intactness or dynamic health.13

The second associated issue is that whatever methodology is utilised, the actions of all private actors will be optimised therearound. While strawmanning slightly here, if a methodology measures the presence of a few key indicator species or vegetational density, the presence of those species or vegetational density will be incentivised — whether those metrics optimise for total ecosystemic health in the long-run or not. Comparisons to the world of big tech flesh this out a little further.

Enshittification

Enshittification, a term coined by Cory Doctorow in 2022, describes the fundamental misalignment in incentives a number of online platforms embody.14 Typically providing their products free-of-charge to end-users, their business models — take Google or Meta as classic examples — rely on the sale of advertising targeting those same end-users. This model requires a business plan that rewards end-users in the early stages of that business’s life cycle to bring them in — to foster high product quality and correspondingly high engagement and ensure the normalisation of the provided product being free. Later, once it is clear that users are unlikely to jump ship and as pressures to grow revenue mount, the needs of advertisers — of actual customers, not end-users — are prioritised.

In the case of Google, ads are shown more prominently, with organic search results downgraded and the search engine optimised to increase the likelihood of users purchasing advertisers’ products. In the case of Meta, ads fill Instagram and Facebook feeds to the greatest possible extent, while content is suggested to maximise time spent on its platforms — not for human connection, as is often claimed, but to maximise engagement with ads. Those on the other end of the pipeline — those producing content on Meta’s platforms or sharing ideas or unadvertised products on Google — are forced to cater the way they do this for those same ends. Content on Instagram has to be made addictive, preying on end-users’ chemically-induced brains. Written content that Google surfaces has to be optimised for its algorithm, an entire industry — SEO optimisation — birthed therefrom.

The entire original proposition of these services’ use — in Google’s case to enable the discovery of ideas and knowledge, and in Meta’s case to foster and enable human connection — gets thrown out of the window; the interests of those actually paying being prioritised and optimised for: the interests of advertisers.

Transposed onto private token- and credit-centric solutions to ecological degradation, the consequences are clear. While seemingly existing to cater to the interests of the natural world, this model caters to the interests of mitigators and compensators — to private actors. Unit prices would be competed down to literally unsustainable levels (regulation-willing), while the outcomes of those units — depending on their methodology — would be the primary aim.15 What would the arc of enshittification in this case look like? In the early days, the lofty goals of nature restoration would stand large, as they do now with existing schemes and high-priest-like peddlers of biodiversity credits. Incentives may seem intuitively aligned — advertising and the intrusive tracking associated therewith, surely, surfaces more relevant results for users? Credit-enabled restoration, surely, puts us in a better situation than we are in today, and at the very least incentivises the restoration of something? But, ultimately, as long as the business model in question does not serve the end-user — differentiated from the relevant product’s customer — the end-user will suffer, sooner or later. The end-user, in this case, is the entirety of Earth’s biosphere.

One key feature of enshittification as a process is the need for market power, which grants product suppliers the ability to degrade their product for end-users while improving it for customers. In the case of nature conservation and restoration, it is unlikely for any one firm to hold market shares and the equivalents of the captive network effects that the likes of Google and Meta enjoy. Regardless, and more importantly, the fundamental mismatch of incentives still applies: because the customer is not the natural world, and without near-debilitating regulation, firms would voluntarily enshittify to compete with one another — to provide a product at terms more competitive than one another. Methodologies, and/or their implementation, would be literally and figuratively cheapened in order to do this.

Implications

A scenario of these misaligned incentives is set out by Ned Beauman’s Venomous Lumpsucker — a novel describing the carbon offsetification of extinction. Motivated by the ongoing sixth mass extinction, countries around the world set up a system wherein companies must pay a fee to wipe a species from the face of the earth, typically via habitat destruction. Intuitively — great! A financial (state-regulated) penalty would discourage extinction-inducing activities. No. A penalty of this kind instead instrumentalises extinction, allowing private actors to weigh the costs and benefits of a particular species on their balance sheets. In the book, reserves were created to optimise for species’ prevalence (as that was the core of this scheme’s methodology), ignoring the broader health of ecosystems and the Earth’s biosphere. And, later, as the digital and biological worlds melded together, the transfer of biological species to digital equivalents was considered part and parcel of the solution.

Venomous Lumpsucker is a satirical work — it is a comedic dystopia, exposing the warped incentives and structures at play in contemporary economic systems. It beautifully elucidates the issues of private solutions to the ecological crises we face: if current economic presumptions are maintained and private solutions are thereby emphasised with existing instrumental logics pursued, the reversal of current ecological trajectories will lead to profound unintended consequences. The natural world would, potentially, be enshittified: after first providing a product to the natural world — its restoration — in seemingly good faith, the actual customers’ — the private actors who pay for it — needs are prioritised. Costs and thereby the product’s quality are pushed down, while the metric in question — based on evolving yet never-complete methodologies — is relentlessly optimised for. This scenario may seem abstract now, but when imagining a scaled-up, lightly-regulated, future where the usage of private biodiversity-credit-esque financing becomes widespread, competition between providers would ultimately cut corners. And in a more heavily-regulated future scenario, private actors may nonetheless ruthlessly optimise to cut corners where possible — the biodiversity-equivalents of tax avoidance: seeking exemptions, claiming deductions, and offshoring income.

The idea of voluntary responsibility under present economic arrangements — the idea of voluntary or lightly-regulated intervention to arrest ecological decline — is clearly bankrupt.16 The idea that private actors will fully internalise the externalities they are causing, and fully pay for natural capital they have previously considered free, is outlandish. The danger of that outlandishness is that some middling half-house solution is the likely end-result — a compromise of sorts, a compromise that would lead to a warped-incentive-ridden system with likely profound unintended consequences. Even under more heavily-regulated scenarios, the same fundamental logic applies: private actors will optimise and enshittify, because that’s what they do — what they are best at.17 They behave and act self-interestedly in incentive-laden environments. And shit follows.18

The Limits of State Intervention

So to avoid the natural world’s enshittification, other solutions are needed. On the other side of the strawmanned coin we find statism — wherein central governments or a central government overseeing geographies of any theoretical form directly embark on nature recovery, funded by taxation of some kind.19 This public solution is the heads to the private’s tails precisely because it acknowledges that the natural world is a public — or rather, depending on the geographical scope of governance, planetary — good that is most efficiently and efficaciously provided for by the state.20 Both in economic schools of thought and political-ideological terms, too, it is the polar opposite of the previously discussed private solution.

It has a number of clear advantages, not least the fact that it escapes the prisoners’ dilemma. If a nation or a group of nations was to fund restoration through general taxation, they would sooner and collectively reap the benefits thereof. They could more easily weather any competitive price disadvantages faced in the short-term and more easily recoup upfront costs in the medium-term. They would, too, be more competitive in the long-run — unlike climate- and carbon-centric action, ecologically-focussed actions’ rewards can be more discretely located within sovereign boundaries.21 Whether political appetite for this avenue is present or not, its benefits are clear.

Frailty

Yet that in no way means it is flawless — far from it. Its weaknesses are numerous, some being potentially fatal. One such weakness has been on display most recently — that of frailty. The political decisions that lead (or don’t lead) to action on ecological degradation often rely on thin majorities and variable public opinion. The EU’s Nature Restoration Regulation, for one, only passed due to the then Austrian Environment Minister Leonore Gewessler’s decision to disobey her government’s directive and vote it through.22 In the EU’s legislative trifecta of the Commission, Parliament, and Council, legislation has to be approved by a qualified majority of member states’ central governments even after passing through the representative Parliament. Gewessler’s decision provided this, pushing through a law thought at the time to be near-dead.

While now on the statute books, the Nature Restoration Regulation’s saga illustrates just how easy it is for long-advocated for and supported legislation to (near-)fail at the final hurdle. A different type of frailty — that of prior decisions being made and unmade — is on display stateside. The executive protection of federal land from exploitation — whether drilling of oil and gas, logging, or development — just as easily becomes executive permission and encouragement therefor. Slightly removed from direct ecological degradation, executive mandates on vehicle emissions and fuel efficiency just as easily become mandates allowing vehicle producers to supposedly self-regulate — abandoning previous targets. And executive support of conservation work abroad can, through a drastic change in administration and corresponding change in ideological priorities, be cut.23

Centralisation and Benevolence

This links to a related weakness of statist interventions in ecological degradation: the degree of risk centralised governance and centralised decision-making entails. While more efficient than decentralised approaches, centralised decision-making can unmake any prior decisions — or make poor decisions in the first place — at any point with greater ease. When singular bodies are responsible for and oversee a matter as strategically important as nature restoration, mitigations that limit the risks of those bodies’ potential unreliability are needed. These can be found in existing state institutions, whether the judiciary, legislature, or executive, but all stand to be challenged by a degrading of norms that uphold them in the first instance — as experienced stateside today.24 These same safeguards, though, could just as easily act as barriers to action as seen in Gewessler’s case — a trait that is less visible in decentralised approaches which emphasise individual interventions.

At the same time, the centralisation exhibited by statism can fall victim to the wholesale application of flawed methodologies. States, even if presumed to be ecologically benevolent, are limited by the same knowledge problem private solutions suffer from — being unable to fully comprehend and act for the natural world. The risk this brings is particularly acute, as that limited knowledge when applied wholly — versus the varied applications private actors might pursue — could either wreak total havoc or bring about complete harmony.25 The underlying assumption of states’ enlightened thinking, too, poses a risk. In the same vein that private actors operate within a set of incentives that typically lead to degradation, states operate within a set of incentives and influences that lead them to making often unwise decisions. One only has to look at the continued sidelining of climate science for clues.26 Politics, no matter the political system a state may adopt, involves the playing off of competing interests with differing strengths — lobby groups, trade unions, and voting blocs — that each have competing priorities. A government is unlikely in any case to transcend politicking of this kind, opting for short-termist, political term-to-political term thinking.27 Statist solutions, too, much like private solutions, ultimately cater to exclusively human interests. They are unlikely to challenge the speciesist logics pervading the planet’s ecologies that our alien visitor observes.

And states’ ecological benevolence is questionable at best. For every intervention that protects and restores the natural world, interventions that degrade and destroy can at the very least be match-named.28 Indonesia’s state-sanctioned move to deforest an area the size of Belgium for bioethanol and food production is one example; the continued conversion of Brazil’s and Argentina’s Cerrado into soy mono-cropland another.29 Closer to home, the disregard England’s soon-to-be-passed Planning and Infrastructure Bill shows for international nature conservation treaties, and the recent dropping of one aspect of the nation’s sustainability-linked farming subsidy, is more evidence still.30

The combined risks of statist intervention — those of political impermanence and of excessive centralisation — create a scenario that is on a fundamental level temporally and spatially mismatched from ecological (and climatic) timelines. The protection and restoration of the natural world is not something that should be reliant on changing political priorities, whether democratically or dictatorially-induced. What for decades have been established norms — the integrity of publicly-funded healthcare in the UK, pacifism in Japan, or the limits of executive power in the US — are being questioned by a mix of populism and circumstance today.31 The century- and millennia-long timelines of nature conservation and restoration are simply incongruous with the ebbs and flows of political will and opinion.

Our Imaginative Deficiencies

Both private and public approaches, then, face limitations. Privately-inclined solutions run the risk of enshittification, with misaligned incentives optimising for misaligned outcomes. Publicly-inclined solutions run the risk of excessive centralisation and simplification — itself not necessarily predisposing poor outcomes, but increasing the risk of poor decisions’ wholesale application.

Privately-inclined solutions would inefficiently and iniquitously provide what is ultimately a public good, something that publicly-inclined solutions are better catered for. The market failure on show throughout recent human history is ultimately a governance failure: the inability of human actors and their institutions to allocate finite resources efficiently and equitably. Yet the forms of economic governance proposed as solutions thereto are insufficient — unimaginatively rooted in Holocene-ic thinking, built to address failures at dramatically smaller scales than the planetary crises we face today.32 Proponents of private solutions are backed by the (un)imaginative default of private capital — capital that holds the power of financial resource allocation, and can thereby paint itself as the only way forward. Proponents of public solutions are backed by the (un)imaginative default of public goods’ provision — the idea that some goods are simply more efficiently provided by the state.33 And each of these defaults does not recognise their respective boundedness: private solutions ultimately cater to the interests of capital; public solutions to the interests of the human public.

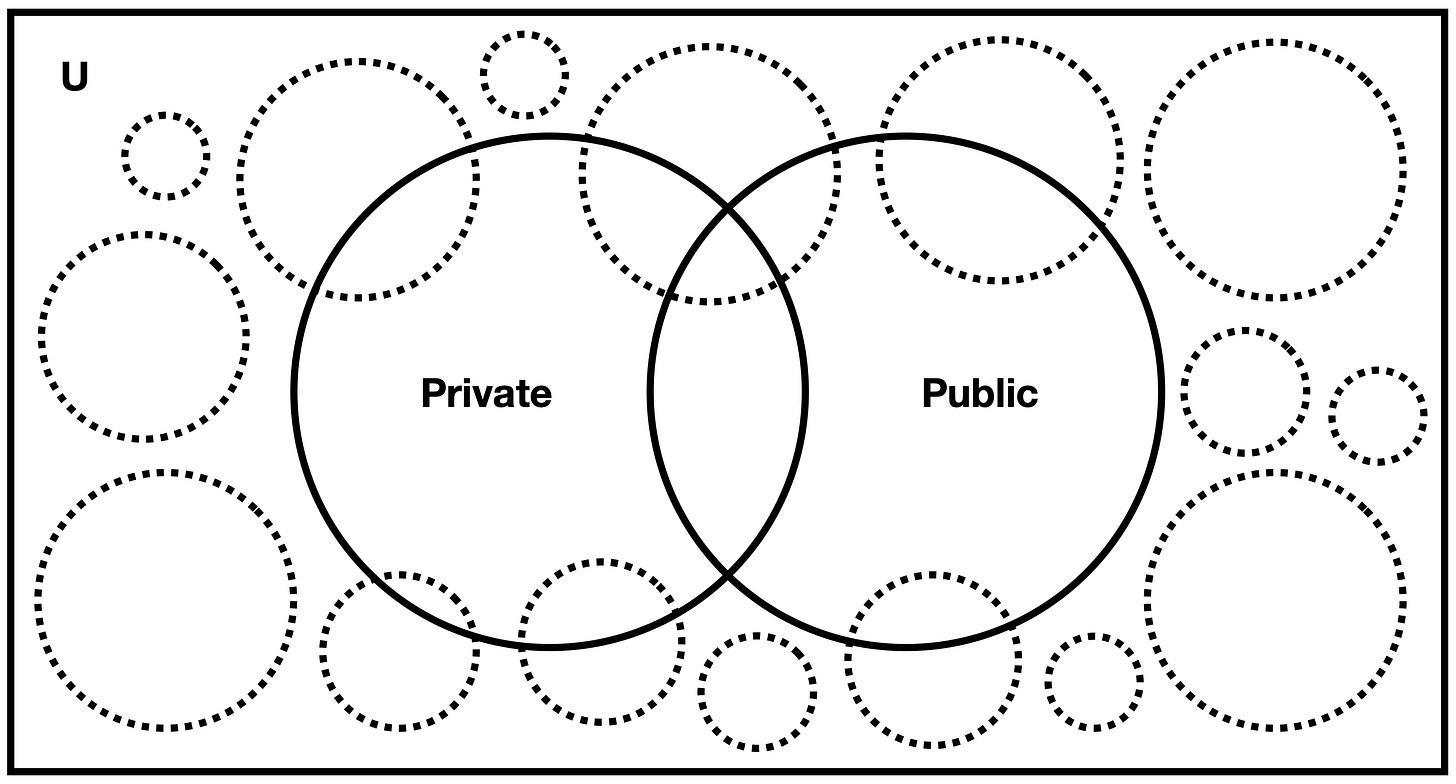

This boundedness is abundantly clear to our cosmic visitor. Defining total imaginative possibilities as a universal set, our current human defaults of private and public interventions fail to capture the range of alternatives — alternatives that we have yet to discover or fashion — on offer. We are self-limited by these interventions’ seeming inevitability, trapped in a sort of bifurcated human fatalism. Existing incentive systems are simply unecological: redefining the universal set as ecologies themselves reveals these systems’ deeply speciesist nature. A number of the critiques made are based on presumptions themselves only present in the private and public sets — they are by no means universal.

This is more an impractical diagnosis than an actionable prescription. Regardless, alternative solutions that escape existing imaginative bounds are necessary: private and public pathways do not suffice. We cannot allow for the natural world’s enshittification by private actors, nor its anthropocentric chopping and changing by states.34 Yet the bifurcated reductive logics described in this essay are by no means limited to these corresponding expressions. Private logics don’t exclusively correlate with marketisation, nor free-marketism. They apply to any pathway that looks to utilise decentralised approaches. While some pathways might place a lesser emphasis on the need to assign economic value on the natural world, other criticisms still apply: the local knowledge problem, and the difficulty of coordinating knowledge and knowing that knowledge in the first place, being paramount. Public logics also don’t exclusively correlate with state interventions: coordinating and concentrating action on ecological crises at inter-actor scales poses the same methodological challenges — particularly those of frailty, risk, and anthropocentric speciesism — no matter the structures pursued.

Notwithstanding these considerations, our cosmic visitor demands solutions. They demand an end to the misery humanity has imposed on the Earth’s biosphere, on its biosphere; on its non-human companions. They demand an end to the narrow, short-sighted, and impotent economic frameworks that continue to wreak havoc. And they demand an end to a historical trend that has disrupted millennia of relative ecological stability.

Clarifications

This essay is descriptive and diagnostic. Its intention is simply to describe the state of things, not to prescribe — precisely because the prescription in question is uncertain, if at all existent.

A follow-up essay examining the prerequisites potential solutions should abide by, though, is in the works. Subscribe to have it land in your inbox as soon as it’s ready!

This is of course an impossibility. It does not, though, limit the utility of the thought experiment.

In general terms, that is. Different human communities of course have differing impacts, and differing levels of foresight.

Or, more realistically, the matching of one human community’s desires with another human community’s ability and willingness to meet them.

The climatic and ecological crises we have caused and face are inextricable. Their separation, here, is purely practical, given the contrast between carbon- and biodiversity-specific solutions.

This comparison was first described by Siobhann Mansel in her How To Make It Good Substack. See the post here.

And arch-enshittifiers like Google and Meta, once their business models are embedded and deeply profitable, resist regulation at every turn.

In the case of England’s water utilities, this is literally the case.

The scale this approach takes can vary, but would intuitively be bounded by nation-state sovereignty. See footnote 32 for more.

On a relative, not absolute, level.

Although this problem is by no means exclusive to statist interventions in nature restoration.

States, here, technically hold the market shares necessary for enshittification to occur. They have a similar mismatch in incentives — catering for human constituents’ interests over those of the natural world. A number of additional misaligned incentives apply too: inefficiencies, corruption, and cronyism, to name a few.

Examples of this abound. In the UK, think of relative cuts to the National Health Service’s budget; or Scotland’s soon-to-be Natural Environment Bill, which enables Scottish Ministers to alter environmental regulations by decree; or EU backtracking on sustainability-related disclosures — now taking place on a domestic level in Germany too.

This holds true on a historical basis too. See James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State.

And each are backed by the idea that private and public solutions are the only scaled alternatives to one another.

While not discussed in this essay, the framing of statism does not necessarily equate to the intervention of exclusively nation-states operating within defined sovereign borders. The logic of centralising statism, instead, is the emphasis.

"The idea that private actors will fully internalise the externalities they are causing, and fully pay for natural capital they have previously considered free, is outlandish" - while this is generally true for the vast majority of firms, the beneficiaries of enormous profits (ie Microsoft, Apple) seem to be doubling down on carbon credits, renewable/nuclear PPAs (power purchasing agreements) and manufacting products with fully recycled** materials. What motivates these corporations to move in that direction? ESG credentials seem very unfashionable today, so maybe it's down to marketing to the climate-conscious? Or is it that, in a shocking move for a public company with quarterly earnings reports, they aknowledge that there won't be a market for much longer if they don't take action to limit their climate impacts? Do these perverse motivations take away from their actions?