An Alternative Land Governance System for Scotland

Welcome back to this blog series on exploring Scotland’s socio- and ecological challenges. Thus far we’ve examined these challenges — namely concentrated landownership and degraded landscapes — and how current approaches seek to address them. We’ve also set up a list of criteria those approaches should be judged by. We’ll now move on to examine an alternative solution. This will be the last post of six, so a special welcome to those who have tuned in from the start!

To prevent repetition by going over existing approaches’ strengths and weaknesses, I would recommend — for those who haven’t already — reading this series in full. Please see each post, in order, for ease below. I would also recommend reading this post in conjunction with the third and fourth for greater clarity.

Community Land Ownership: The Solution to Scotland's Socio- and Ecological Challenges?

Private Purchase: The Solution to Scotland's Socio- and Ecological Challenges?

A thought experiment that I like to use, and that I feel would be apt here, is that of the cosmic visitor. Think of an alien — embodying a detached, objective, observer — coming down to earth and expressing judgement of the systems and structures we use to organise ourselves. Unaffected by the contingencies and baggage of history, what would that visitor make of our land governance structures? What would they make of a system that inefficiently, iniquitously, and unecologically places ownership and subsequent control in the hands of a few individuals; what would they make of a system that dispossesses, disempowers, and subjugates a landscape’s human and non-human inhabitants? It is hard to imagine they would view these structures kindly — structures that, in effect, pervade the status quo.

But this is just a thought experiment. It isn’t particularly practical, and could lead us to unproductively conclude that everything is flawed and should be rebuilt from the ground up. While not entirely untrue, taking this view disregards how change, particularly in land governance, occurs. Bar catastrophic events that induce major societal shifts — whether war, uncontrolled pandemics, or serious famine — change is gradual. It results from successive responses to sociological, political, and environmental contexts, much like how a species may evolve within its ecological context reflexively. The problem with this dynamic is that the power that landownership affords can manipulate both what is responded to — through altering contextual conditions — and how it is responded to — by altering social and cultural debate in the power holders’ favour.

Bar a catastrophe, then, incremental change is the way forward. This does not, though, presuppose incrementalism — it does not speak to an excused lack of action. Incremental change is about responding to current contexts with an eye on the future; about creating the conditions for a cascade of subsequent changes through a systems-level realignment of incentives. With this in mind, let’s get into it.

The dichotomous approaches of communal and private can be married. Responding to the urgency of nature restoration and sociological realignment, their strengths can be combined and their weaknesses overcome to establish a system of landownership that more accurately reflects the needs of the present-day. That new system would not be established in absolute, but instead eased in through comprehensive purchase of existing landholdings — to be governed under a novel framework that separates legal and equitable ownership; that separates the ability to decide and the ability to profit or lose off of those decisions.

In scaling nature restoration-centric land acquisition, and in establishing structures conducive with long-term systemic cascades, the communal approach’s benefits are clear. The Land Reform Act’s provisions for pre-emption rights on and compulsory purchase of land provide a path through which a well-funded actor could overcome the issue of land liquidity — transferring parcels from unsympathetic or less-than-sympathetic landowners to kinder hands. It would additionally allow that actor to strategically map and acquire areas desirable for nature restoration projects, instead of purchasing plots that sporadically and unpredictably go up for sale, on- or off-market. The Act, then, is there to be capitalised on — its shrewd and judicious use could go some way to increase its paltry impacts on landownership distribution.1 Primarily, though, the communal approach draws its strength through in-built legitimacy. It offers a clear benefit in its level of agency and devolved control: decisions are made by those affected by their consequences.

The private approach’s main strength comes in its practical scaleability. Funding is more plentiful than that available for the communal, and concurrent expertise to manage scaled acquisition and subsequent management is prevalent too. This, of course, is dependent on appropriate nature restoration financing being ironed out in the coming years — a genuine uncertainty at this point in time.2 It is also dependent on the grade and integrity of nature restoration financing expanding — going beyond Woodland and Peatland Code-centred project portfolios.3 The coming Ecosystem Restoration Code may do this, but it is again an uncertainty.

And while the communal and private approaches have much to offer and complement each other with, neither address the more significant questions that will affect Scotland’s socio- and ecological wellbeing in the long-term: overcoming excessive agglomeration and disagglomeration; overcoming parcellisation; implementing durable and dynamic protection measures for restored land; and developing structures that could integrate non-human voices into land-use decision-making.

For the sake of simplicity, the proposed alternative entails the founding of a central funding vehicle. That vehicle would likely be incorporated as a trust — one dedicated to nature restoration-centric land acquisition, predicated on the fact that nature restoration-centric land use will likely entail higher yields than present management does.4 A trust is preferred over other instruments because of its inherent flexibility. It allows for the provision of additional duties, beyond those prescribed by legislation, that trustees must abide by and beneficiaries must agree to. A set of principles or specific guidance, for example, on acting in the interests of the natural world, can be inserted, and a set of tailored rules on capital raising and withdrawal can be implemented too.5

Profit maximisation would not, here, take precedence. I won’t go into fundraising structures in too great a depth as it isn’t the focus of this series, but patient investment from large funding bodies, beyond British pension funds seeking high single-digit yields, would be sought. Bodies that aim for a lower-than-average but steady return; want to inset large carbon footprints from their portfolios; and are able to work on multi-decadal, near-half-century time horizons, would be prioritised. Funds like Singapore’s GIC, which averages an annualised real return of about four-and-a-half percent, is an example of this. Relatedly, land in Scotland will likely become a refuge for capital in the coming years. A durable asset class in a politically stable country is increasingly rare in a geopolitically uncertain world — the healthy appreciation in land values in recent decades is thus likely to continue.

So — a central funding vehicle, incorporated as a trust, with specific provisions that require trustees to act beyond the immediate financial interests of beneficiaries. This forms the top layer of the proposed structure. The base layer — although the use of the word base should by no means diminish its importance or standing — would be formed by incorporated community groups. Community bodies who wish to pursue the legal mechanisms set out by the Land Reform Act must be incorporated in a geographically-delimited manner — defined as communities of place, whether that be by postcode unit, electoral ward, locality, or landmass.6 Membership of these bodies is then open to all who live in that place. Crucially, too, when Parts 2, 3A, and 5 of the Land Reform Act are pursued, whole-place votes are held outwith the community body, meaning that all are involved in the decision to purchase land regardless of membership status.

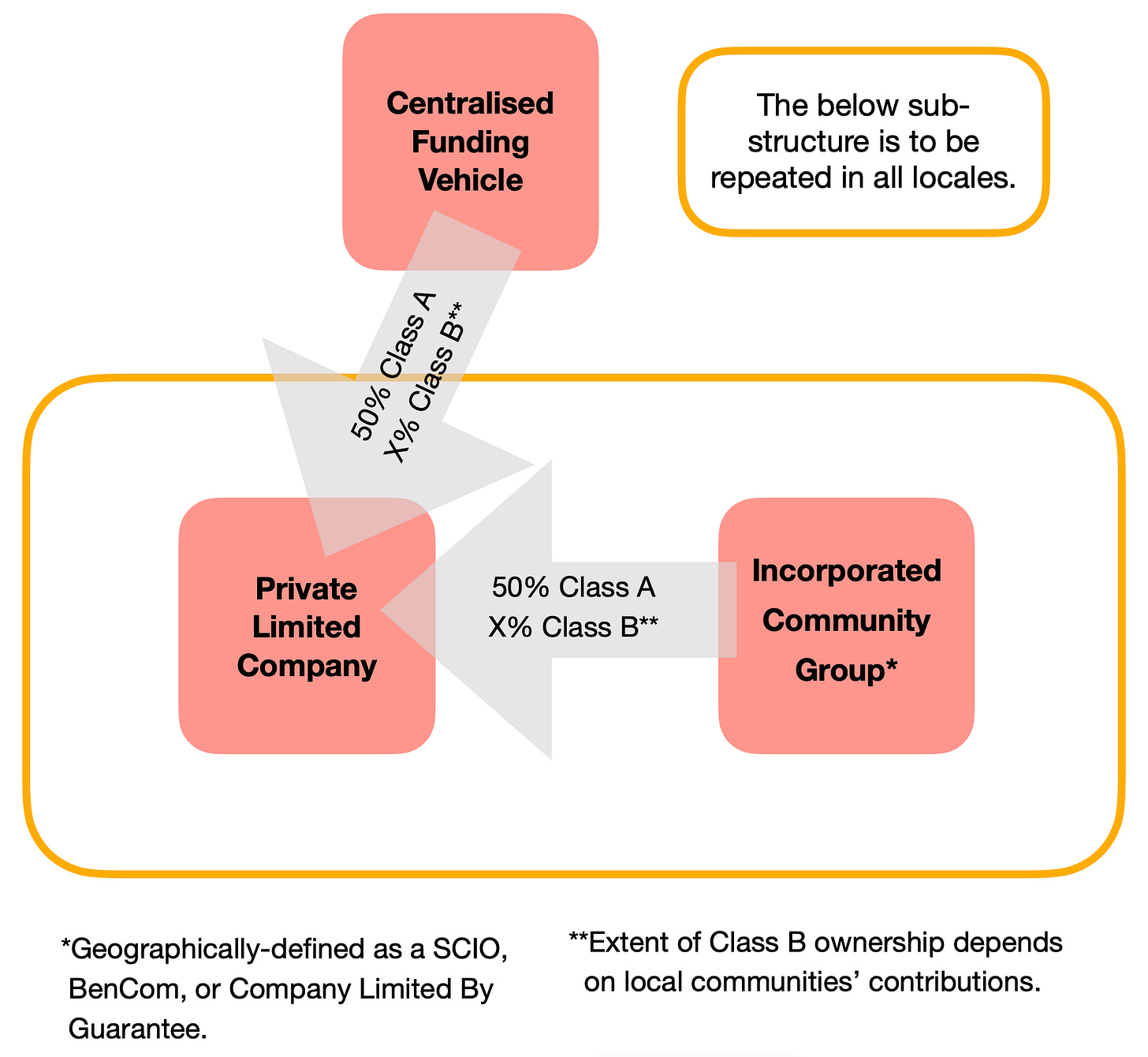

The interface between these ‘top’ and ‘base’ layers would be a set of private limited companies incorporated in line with the geographical delimitations presented by each respective community body — each body thus having a matching company. Those companies would have dual-share classes. Class A shares would have full voting rights with no equity. Class B shares would have no voting rights but full equity.7 Class A shares would be split evenly between the community body in question and the central funding vehicle, in accordance with the legal advantages community bodies offer in land acquisition and in accordance with the financing provided by the central funding vehicle. Class B shares would be split according to financial contribution — so, presumably, the majority would go to the central funding vehicle but some may be granted to the community body on a gratuitous basis.8 Community bodies could raise funds independently too, and contribute accordingly. These private limited companies would have additional provisions in their articles of association that require adherence to nature restoration and maintenance as a core principle, beyond simple profit maximisation. These companies’ boards, too, would not have their representation split down the middle — with half acting in the interests of the community body and the other half the central funding vehicle’s. They would instead consist of agreed-upon independent third-parties to prevent potential deadlock in regular decision-making processes.

This, in written form, sounds rather convoluted, so I’ve fashioned a diagram for ease. I would be more than happy to elaborate on any aspects readers might be unfamiliar or uncomfortable with in the comments down below, so please don’t hesitate to ask!

Let us, then, judge this solution by the criteria we have set out previously.

1. Levels of Agglomerated and Disagglomerated Control

How does it rate on levels of agglomeration and disagglomeration? Fairly well — balanced agglomeration and disagglomeration is inherent in its structure by distributing power amongst bonded yet separate actors. It avoids excessive centralisation but similarly avoids excessive decentralisation. The central funding vehicle offers central oversight in accordance with a set of appropriate principles, but is only able to make land-use decisions alongside each incorporated community group — and vice versa. This distribution of control adds resiliency and redundancy to the system, and prevents universal application of decisions that may prove inappropriate in the long-run. It creates a sense of dynamism, of specific responses to the specific ecological needs of a specific place without forgoing the overarching needs of the ecological whole.

2. Overcoming Parcellisation

How does it rate on levels of parcellisation? Really well. In theory, this model allows for strategic acquisition of land across Scotland. Priority areas for nature restoration can be mapped and targeted through judicious use of pre-emption rights and, potentially, compulsory purchase.9 Swathes of connecting plots of land can be targeted directly too, forming networks throughout the country.

3. Addressing Concentrated Landownership

How does it rate on addressing concentrated landownership and associated sociological ills? Better than the status quo — which currently entails a further narrowing and cementing of iniquitous ownership distributions. Importantly, the status quo additionally entails a complete loss of agency and a complete loss of equity: beyond minimal employment, little is offered. This model provides a strong sense of agency — a veto right, essentially, on land-use decisions — and a higher probability of claiming equity.10 Most importantly, though, this model’s success is predicated entirely upon communities’ agential decisions to participate: should they be unwilling to, it would not go forward.

4. Long-Term Protection Measures

How does it rate on long-term protection measures? Better than the status quo. By distributing ownership and control, contravention of restoration objectives becomes more difficult. What this model offers is a dynamic, responsive, structure with a variety of actors and interests that act in accordance with a set of overarching principles. Instead of one or two actors — be they the owner of a bit of land or a responsible body with which a conservation burden is registered — having control, a distributed system of organisations, each with their own ‘membership’, would be required to reverse decisions. This also increases the number of potential enforcers should any one element in the system not be acting in accordance with overarching objectives — instead of a responsible body that may have limited capacity, or a court system that may have to allocate and prioritise resources elsewhere. The incentives that this model creates, too, separates decisions from their propensity to make a subsequent profit or loss.

5. Practical Scaleability

Finally, how does it rate on scaleability? Here, it is middling. Funding models aside, its proposition is more practical than that of the private or communal approaches — it combines ample financing with the legal means to acquire land. Its challenges, if anything, lie in convincing potential stakeholders that this is the case. The model is abstract, untested, and foreign in a system of landownership that accepts absolute dominion as standard. It relies entirely on the goodwill of participating communities, and relies entirely on the risk appetite of investors to put capital into an ownership structure that surrenders partial control over that capital’s allocation. It similarly relies on an alignment of priorities — namely on nature restoration. That is not to say, though, that convincing these stakeholders is an impossibility. The benefits to both ‘parties’ are clear: communities attain a previously impossible degree of meaningful agency, and investors are able to invest capital in volumes that increases economies of scale and overcomes the sociopolitical barriers of land acquisition and corresponding ownership concentration. This just needs to be communicated lucidly and convincingly.

One additional criterion that I added to our list last week was that of ecological democracy — of the idea that land-use decisions should be made according to the needs of all affected actors, human and non-human. Here, this model and approach don’t explicitly align, beyond assurances that decisions are made in accordance with the natural world’s priorities. What it does do, though, is open an avenue for eventual non-human democratic participation. It de-essentialises the absolute dominion presupposed by landownership. And while crude, the nature of share ownership means that non-human voices could be integrated directly into decision-making processes down the line, much like attempts to integrate the rights of nature around the world tend to place responsibility on representative individuals and bodies.11 This model would give that kind of representation teeth.

Removed from the Scottish context and specific legal provisions that make strategic land acquisition easier, this model is applicable elsewhere. A distributed system of landownership and control would do wonders around the world, and all countries and regions face challenges similar to Scotland’s — just to differing, and usually lesser, degrees.

Edit (14/01/2025): While it does redefine landownership to some extent, this governance model would partly fall victim to an alien observer’s criticism. Dual-class share structures are deeply unecological — a figment of human imaginations if anything — and aren’t exactly what you’d want to see managing land in 200 years time. The model also doesn’t actually alter the fact that land is owned in the first place: it reinforces the dominion presupposed by human legal superstructures. On these points, it is important to keep in mind that the model proposed is essentially a stopgap: a reasoned response to present contexts and needs. In addition, it offers a pathway out of the current presumption of dominion. It introduces a flexible and adaptable governance structure capable of integrating non-human voices down the line, and capable of altering the way land is owned and transacted. This is in no way offered by the status quo. Land is not owned and controlled in the traditional sense — no matter who the beneficiaries of the trust which holds class B shares are, their preferences cannot be implemented wholesale given the safeguards layered throughout. Land would not be sold either, assuming the community and trust wish to retain control — class B shares would be sold instead: shares with a protective wrapper that presumes particular management and exhibits particular resale requirements. Sympathetic land-use, then, would be secured in perpetuity without complex deed-based mechanisms — the same is true of the class A shares structure used to make land-use decisions: this would remain the same despite changes in equitable ownership.

So — that brings us to the end of this blog series. Do share your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments below or by email. I’d love to hear from you, and I’d love to hear what you make of the alternative solution proposed in this post.

Thank you, truly, for tuning in and for sharing the series with your friends, family, and colleagues. I’ll be writing a few more pieces on adjacent matters in the coming months, so if you’d like to stay in the loop please do subscribe directly to this Substack. Until then, I hope you have a restful and rejuvenating holiday season!

Image Credit to Joe Payne, a good friend of mine and a great landscape photographer! See his Flickr and IG for more.

Please refer to the third post in the series for more details on this matter.

Refer to the fourth post in the series for more on this.

Existing scaleable project pipelines often focus on sub-standard restoration objectives reliant on the carbon-centric Woodland Code. Refer to the fourth post in the series for more on this.

This is a presumption, but given current estate management practices typically make a loss or yields in the low single-digits, it is not hard to imagine this will be the case.

This approach is taken by the previously mentioned Barrahormid Trust, a participant in Highlands Rewilding’s NCIP model. The difference here is that there is no single point of failure, and a greater number of points of enforcement.

They must also incorporate as a SCIO (a Scottish charity), a Company Limited By Guarantee, or as a BenCom (a Community Benefit Society) to qualify.

To be clear, share classes don’t exist in a strict sense. A and B here are used to simplify matters, but the rights of specific share types can be outlined in the articles of association of the private limited companies, and can go into great depth. A and B are used to simply differentiate between voting and yielding shares.

Edit (12/01/2025): Gratuitous may be the wrong term here. Payment can be made in recognition of the legal advantages community groups offer through the Land Reform Acts. Whether acquired throughs Parts 2, 3A, or 5, a plot’s valuation is carried out by an independent appointed third-party: this means that when purchasing land systematically, artificial, rigged, price increases can be mitigated against. Communities’ participation, then, has a demonstrable cash value in this sense.

As discussed in the third post of the series, compulsory purchase as defined by the Land Reform Act is a legally untested and risky approach for this purpose. It is regardless worth being mentioned.

Here I am inspired by Alastair McIntosh’s work. See this paper of his for more.

One notable example is that of the Whanganui River in New Zealand.